Lisa Tree Rings

minerva vitti

(venezuela)

In the midst of defending ancestral territories and caring for the family, many indigenous women leaders are the last in line for their own rights. Their bodies, the first territory inhabited by them, are the first to get sick. Through the story of Lisa Henrito, a Pemon indigenous woman and defender of the land in the Venezuelan Amazon, we delve into an intimate and political story that portrays the need to generate processes of self-care and care as a strategy of resilience and resistance, for the individual well-being of the defenders of the land and the survival of the movements, which have been facing the extractivist projects of the Venezuelan government and the violence of the multiple armed actors in their ancestral territories for years. The climate crisis is also a crisis of care for the defenders of the earth. – Minerva Vitti Rodriguez

1

“These gangsters are there, it provokes throwing a bomb at them, but I have to calm down,” says Lisa Henrito Percy, defender of the land, when we pass in front of some trucks loaded with food, which are parked on one of the streets of Santa Elena de Uairén, capital of the Gran Sabana municipality, southeast of Bolívar state, Venezuela. Ella’s brother Lenon drives the car in which we moved. Minutes later we entered the town of Manak Krü where the headquarters of the Council of General Caciques of the Pemon People are: “Before, the people used to come, it was more important than the mayor’s office,” she comments disappointedly, and when she looks back at the community cemetery she remembers that the place has become a corridor for Venezuelan forced migrants fleeing the complex humanitarian emergency plaguing the country: “A man died of a heart attack while walking. The family looked for the papers to bury him here and continue his journey to Argentina. What we are experiencing is very sad.”

We leave the town and take trunk 10 that connects Venezuela with Brazil. At the height of the El Escamoto Military Fort, Lisa resumes the story that she is telling in fragments: “Here we lock up. They came with tanks. They wanted to wipe out the town.” On one side of the road there are some lands bordered with wooden sticks and wires: “The indigenous communities are fencing off their lands due to the invasions,” adds the leader of the Pemon indigenous people. That’s what she was working on today.

She is already starting to get dark and on the other side of the border, already in Pacaraima, Brazil, we look for some diapers for her father. There are queues for gasoline, most of the cars coming from Venezuela. The incandescent lights of the premises illuminate the streets full of cars, holes and people. The conversations are in Spanish, Portuguese and Portuñol (a mixture of both languages). Traffic is heavy so Lenon parks and we get out.

Dressed in patterned pants, black flannel, high-heeled sandals, and a small crossbody bag, Lisa wanders through various stores crammed with bales of food until she finds the right size and brand of diapers, which she and her two brothers take turns making. purchase. She hugs the bagless package like it’s a newborn baby and we head back to the car.

Before entering Venezuelan territory again, we passed one of the shelters where Warao migrants and refugees live, another indigenous people whose ancestral territory is in Venezuela, but who fled to survive.

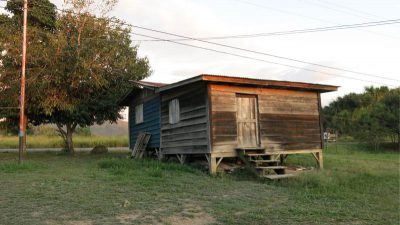

When we arrive at Lisa’s house there are “strange people” filling some water drums in the river. “Did they ask permission?” she asks them with authority. After dispatching them she places me in a small wooden house, which she calls her batcave. I order my things, I take a bath in a restroom in the middle of the mountain and I look for Lisa who is taking care of her father.

The man remains in a fetal position on a bed surrounded by a mosquito net, groans slightly. “It’s very cold here,” says the daughter as if deciphering her lament and begins to put sheets on top of the net, pressing them with clothespins until everything looks like a tent.

We dined on arepas with cheese and a drink made from cereals and corn that the Adventist missionaries gave them. It is almost eight o’clock at night on October 3, 2019 and the day for this defender continues. She must go to Manak Krü to meet with the team from the indigenous captaincy of sector 6 of the Pemon people.

Lisa says that she gets up early to feed her mother’s chickens, that at the moment she is traveling with another of her children; She later goes back to sleep “because of the cold” and because after the massacres perpetrated in her territory she was left with a lot of insomnia. It’s barely been three weeks since she went back out on the street.

Only three hours have passed and a part of the Venezuelan Amazon and its complex reality opens up before our eyes: co-optation of traditional indigenous organizations, passage of Venezuelan migrants and refugees fleeing the country’s crisis, repression, dispossession and militarization of indigenous territories, family care.

The Gran Sabana in a woman.

Lisa sneezes several times, we say goodbye and she walks into the darkness of the road planted with moriche trees.

2

All the names in his family begin with L: Lloyd, Leonisa, Lenon, Leodan, Lisa.

“Our names are a reflection of who we are. The influence of the missionaries on my parents, that meeting when the Adventists entered the lands of what is now the Gran Sabana, the clash with the Catholics. My name is not indigenous, it is rather a gringo, but it sums up who I am, my upbringing, my family, the history of my ancestors. Many names are imposed, for example González is a surname that the military placed. It was easier to identify the indigenous, if they worked with three brothers, they called them González. Is incredible. So you look up your family tree and think: Dick! Where did this name come from? says Lisa Lynn Henrito Percy, eldest daughter of the first Pemon Adventist pastor who graduated in theology.

Geography becomes genealogy and the Wadakapiapotepui, a tree in the center of the world that bore all the fruits, continues to be the protagonist of the ancestral story that speaks about the abundance of food for its people and the flood that was unleashed when it was cut down. In front of her blue body flow Lisa’s roots, the same ones of the Pemon indigenous people, which cover the different territories of the center and southeast of Bolívar state, in Venezuela; as well as neighboring areas of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana and Brazil, a territorial extension of not less than 85,000 km².

This is the Wadakapiapo-tepui. The tepui or tepui are the oldest exposed formations on the planet, their origin dates back to the Precambrian and they are found in the Guiana Shield. Photo: Minerva Vitti.

“My maternal great-grandmother is from Mowak, Kavanayen area. My maternal great-grandfather was kidnapped when he was a baby by the Pemon Arekuna during the last war. My paternal great-grandparents are from Luepa. My maternal grandmother was born in Wanakpupay, in the San Rafael de Kamoiran area. My maternal grandfather was born in Mowak. My paternal grandfather was born in Luepa. My paternal grandmother was born in Cuyuní. My dad was born in Paruima and my mom was born in Apoipo—Lisa unfurls her branches.

The word pemon means person. According to the 2011 Census, there are 30,148 Pemon indigenous people, divided into three subgroups: Arekuna, Kamarakoto, Taurepán, making them the fourth largest indigenous people in Venezuela. In this country they develop their existence in an area of approximately 38,000 km², distributed in 183 communities organized in 8 indigenous sectors, located in the Angostura, Piar, Sifontes and Gran Sabana municipalities, the latter formed by 6 sectors.

Genealogical data is not always simple, especially if you belong to an indigenous people that is at least 5,000 years old, but there are other things that are more difficult.

Lisa Henrito has been criminalized by the military high command for promoting a secessionist movement in the south of the country. The accusation was made by Brigadier General Roberto González Cárdenas in a national television program and broadcast by the Telesur network, on July 23, 2018, who also accused her of being a foreigner for having been born in the indigenous community of Paruima, in Guyanese.

Due to these complaints, Amnesty International issued an Urgent Action the same year to protect the leader. The document explains that she “is being stigmatized for her work as an activist for Pemon indigenous women’s organizations that demand an end to the militarization and mining of their ancestral territories without informed consultation or prior social impact studies.” . A year later, Lisa also responded.

Lisa’s swearing in as Maurak’s captain. Photo: courtesy of Lisa Henrito.

Extractive activity has increased in a disorderly and violent manner throughout the region south of the Orinoco River (Amazonas and Bolívar states), since President Nicolás Maduro unilaterally approved the Orinoco Mining Arch National Strategic Development Zone, which authorizes the exploitation of minerals such as gold, bauxite, iron, copper, coltan, diamonds and rare earths, in 12% of the national territory (north of Bolívar state and special block in the indigenous community of Ikabarú); and that also creates the Military Limited Company of Mining, Oil and Gas Industries (Camimpeg)

The Orinoco Mining Arc directly overlaps with the ancestral territories of the Mapoyo, Inga, Kariña, Arawak and Akawako indigenous peoples, and its area of influence includes the homelands of the Yekwana, Sanemá, Pemon, Waike, Sapé, Eñepá and Hoti o Jodi in Bolívar state; the Yabarana, Hoti and Wotjuja, in Amazonas, and the Warao, in Delta Amacuro.

—Sector 6 is the stone in the shoe because it resists the government from coming in and doing what it did in Sifontes. You who have traveled, tell me if there is ecological mining, if there are clean rivers. No. That does not exist. The government sees what the captains want and co-opts there. I who fight against the government cannot have a tail and straw, they are not going to use me—Lisa gets upset.

Vladimir Aguilar, lawyer and coordinator of the Working Group and Indigenous Affairs (GTAI) of the Universidad de los Andes, maintains that the only thing that is leading to the secession of the country is the idea of res nullius (nobody’s thing) that implicitly implies the Arco Minero del Orinoco: “The main guardians of the national territory are the indigenous people, and in the case of Guayana, the Pemon people, based on the new notion of security and defense contained in articles 326 and 327 of the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (CRBV) which recognize protected areas and indigenous habitats as key spaces for territorial integrity in border areas”.

Lisa and the Pemon people have protested against megaprojects such as the National Tourism Company of the South (Turisur) Hotel Complex (1995), Power Lines (1997-2001), Decree 1,850 that authorizes mining in the Sierra de Imataca (1998), Gas Pipeline Transcontinental (2006), Satellite Communications Sub-Station in Luepa (2007-2008), Decree 2,248 authorizing the Orinoco Mining Arc National Strategic Development Zone (2016), among others, for going against the rights of peoples indigenous and nature. In none of these, the Venezuelan State has complied with the prior, free and informed consultation processes, stipulated in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), nor the socio-environmental impact studies stipulated both in national legislation and in the international treaties that the country has signed, also develop on a highly disputed territory for gold.

The self-determination of the Pemon people represents an obstacle to the extractivist projects of the national government and the indigenous jurisdiction becomes the last stronghold of indigenous resistance in a country plagued by legal dissidence. “This is based on the principle of administering justice but also managing their territories to guarantee their ‘forms of life’, or what is the same, their living spaces,” explains Aguilar.

Pemon boys and girls wake up with ancestral stories embodied in their daily lives. Photo: Minerva Vitti.

However, many of the sectors into which the Pemon people are divided have been opened up to mining activities. Becoming miners has been one of the resources to protect their territories, their ways of life, self-support and themselves from territorial dispossession, although this decision is far from being the end of the problems for the Pemon and it is not shared by all the communities either. .

Currently, the leader repeats as captain in the indigenous community of Maurak, a position that she held between 2002 and 2005 and in which she was elected again for the period 2021-2025. The process was difficult, because most of the residents know that she is very critical of the policies of the current government, and they consider that this could put her and the community at risk.

“Let no one forget why and what we are here for,” she said during the swearing-in ceremony on January 5, 2021, wearing her plume of blue and red macaw feathers, a privilege only held by some male leaders on the continent. .

Lisa has also been given a baton, which symbolizes ultimate authority.

From her first leadership, she still remembers how she got sick of the pressure and implication that the position of captain demands in a community.

3

The whole night of the first day it rained. The drops rushed violently on the zinc roof. Over the sound of the water was mounted the song of an outdated rooster and that of hundreds of crickets and toads celebrating the great deluge. Lisa returned almost at eleven. She knew because she knocked on the door to tell me how to turn off the only light bulb that illuminates the Batcave. These days she will stay at her parents’ house which is right next to her.

Lisa lives inside a tree, her cave is made of wood, raised a few centimeters from the ground. This is how the Pemon of Guyana build it. It has two spaces. One where the bed is protected by a mosquito net, three plastic tables, wooden drawers; and another with drums and other tools to cut down conuco. On the tables are a damaged computer and a suitcase with all his clothes. In the drawers: four pairs of boots, four pairs of sandals, some magazines, books, and the pack of diapers her father uses. The curtains that cover the windows are white with red flowers and orange butterflies.

Remembering and living that what is private is public is essential to take care of ourselves. Photos:

Minerva Vitti.

A stuffed boar named Jorge rests on top of the bed. “You do have strange tastes,” a friend once told her in the office. On another occasion they showed the boar to a baby to calm him down and he became more frightened. Lisa always laughs telling this story. She also had a stuffed donkey named Orlando.

On the wall next to the door there is a shelf with a felt shirt from Peru, a drum from Argentina, some ceramic houses from Coro, moisturizing creams, toilet soap, a small photo frame with a photo of her father and another larger one with the photo of both parents covered in one corner by a Lisa passport size. “My dad is my dad and I’m his girl,” she tells me one afternoon as she shows me the portrait.

The large frame has a small plate with the face of the Guaicapuro cacique and from each end of the frame hang two anklets made with beads and kewey seeds, they are for the protection of his steps.

This is the batcave of this defender. The only space of intimacy of her.

At 7:20 in the morning, Lisa walks into the chicken coop next to the bathroom. She is wearing a T-shirt and shorts that show off her short legs. Her long black hair falls like branches on her jasper skin. Today he woke up with a sore throat.

—I have to take care of this hen, she is very stubborn, I put her in the house and she gets out. A sparrow hawk passed by and took one of the chicks, now there are five left,” she says with a swollen face.

Several kau kau (birds) perch on a rope and fly towards the huge mango tree. Beneath this there is a tube connected to a hose that must be dragged to the bathroom in order to have water. I count five houses. All of wood, all raised a few inches off the ground. We are surrounded by kuay (moriche) trees. A small river, the Uairén, crosses the savannah. Someone throws a lid off a car and the sound spreads. If we were not on the side of the road, only the chickens, the birds, the parrots and the river would be heard.

Tuenkaron is a character who lives in the waters, rivers and streams. She is a small, long-haired, pretty woman. She takes care of nature and punishes those who desecrate it. Photo: Minerva Vitti.

After a while a neighbor arrives to tell us that last night she heard noises in the house that is being built for Lisa’s mother and father: “They turned on the lights around four in the morning,” the woman specifies. We walk to the place. Inside there is cement, blocks, rebar, plastic tubes… There are also boxes full of books on theology, leadership, self-esteem, psychology of Lisa’s father. Nothing has been taken.

We return to the house and some relatives of the defender arrive.

“This is always the case,” she says as we sit down to breakfast. For a moment, she forgets what she is eating and points to a motorized pump that she has seized and that is just under an inn— It is the one that the government is distributing for mining— Lisa explains to me.

There is a difference between indigenous mining communities and indigenous communities in mining areas. In the second case, it can be said that some of the places that today are mines controlled by the indigenous people, before they were in the hands of mafias and later of the military, it was not a practice of the indigenous people, a third party opened it in their territory, affecting life of the indigenous. This does not free the Pemon people from observations, criticism, and above all danger: many indigenous people are buried in the midst of landslides in illegal mines, get sick with malaria or are disappeared and killed by criminal groups and state agents who control the activity.

The foregoing shows that when the experiences of self-management of resources of the indigenous peoples and communities are based on extractivist businesses, the war and the multiple interests around these economies do not admit that they are owners, they only accept them as victims and even as victimizers. The latter is the case of the opinion matrix surrounding some of the members of the Council of General Caciques of the Pemon People, who have been co-opted by the government; or of Pemon indigenous people who have mines and are criminalized by some academics under the fallacy of “Indigenous Mining Arch”.

—Look, this is Jazmín, my niece— Lisa introduces me to the protagonist of the article she wrote on the days of the Kumarakapay massacre in 2019 and which she titled: “My niece was screaming, I don’t want to die”— Maurak is the community where there were more displaced, they were afraid that they would attack again, many families were separated, my nephews left. There they have a mixture in their mind: “How do you say hello in Portuguese?”. “In my country you don’t eat that.” The children play to kill Maduro because they say that he took away their land and now they live in a dry place, without water.

Many Pemon refugee families in Brazil decided to stay so that their children would have better access to education. Photo: Minerva Vitti.

The defender is sad but distracted again when she sees her mother’s chickens pecking around the house.

—Oh no, those chicks are a nightmare. What’s more, I’m going to cook rice for them right now— she gets up and walks to Lloyd’s bed— Come on dad, I’m sure you’re hungry too.

Yes, I think everyone is hungry.

4

My Father

I have a loving father

He’s so loving as a mother

His best colour his blue…

The poem is called My Father and Lisa wrote it when she was eleven years old. She speaks, reads and writes in three languages: English, Spanish and Pemon Taurepán. She also understands and communicates in Portuguese. Throughout her basic and secondary education, which was mainly in Guyana, she was always a very good student and won scholarships. In fact, to enter the high school that she did in Georgetown, the capital of this country, she took a test conducted among all students nationwide and was selected among the top ten places. The subjects that she liked the most were English, Caribbean History and Biology.

The multiple trips of her father Lloyd Henrito, the first Pemon Adventist pastor to graduate in theology, made the Henrito Percy family live five years in Trinidad and Tobago, twelve years in Guyana, until they finally settled in Venezuela.

—When I was four years old they took me to a psychologist because he stuttered. The doctor said that my brain was very fast and wanted to say everything at once. I was also in piano lessons but because of the trips I couldn’t continue,” recalls the defender.

Lisa and her family moved many times due to her father’s theology studies. Photos: courtesy of Lisa Henrito.

When they returned from Trinidad and Tobago to Guyana, Lisa and her siblings lived with their grandparents in Paruima. At that time, she was seven years old and learned some elements of her culture, such as her first words in Taurepán, although she says that she speaks Taurecuna (taurepán and arecuna). They also went to the conuco on Mondays and returned on Fridays. Lisa cried a lot because she wanted to be with her parents, who were constantly traveling because of her responsibilities in the Adventist Church.

During high school in Georgetown, Lisa and her siblings lived in family homes, but during vacations they would join her parents in Lethem, a community on the border with Guyana and Brazil where Wapishana, Macushí, English and Spanish are spoken. Portuguese.

By the time Lisa arrives in Venezuela, she is already 18 years old and enters the Adventist University Institute of Venezuela, in Nirgua, Yaracuy state, where she studies Business Administration for six years; and every time she has vacations she travels to the south of Bolívar where her parents and her brothers settle.

—When I returned I spent a year and a half with a very strong personal and cultural conflict due to the language problem. At the university I lost a semester because of the theoretical subjects, I scratched them because I didn’t know Spanish. My first language is English and despite having been with my grandparents from seven to eleven years old, I did not speak Taurepán or Spanish. Our holidays were in Lethem where these languages were not spoken either. You can imagine all the mixtures, all the cultural impact. On the one hand it was good, but returning to Venezuela came the shock.

The defender says that even within the country they moved several times, which made the situation more complex.

—The crisis was strong because one learns one thing in one place, then we move to another and the expressions are different in arekuna and taurepan, if he said something people would laugh because it wasn’t like that, it was very strong, but I got over it . One thing I like is that here in Venezuela the roots of the indigenous language are strong.

This language barrier never made her doubt her indigenous origin, she grew up listening to the stories of her ancestors that her mother told her. So she learned the language in the community, talking to the people.

On her part, English and her studies at her university allowed her to access jobs that she would never have considered. One of them was as an administrator at Placer Dome Technical Services, a Canadian mining company that, together with the Venezuelan Corporation of Guayana (CVG), formed the company MINCA (Minera Las Cristinas) to exploit the Las Cristinas mine, in Bolívar state.

Lisa came to this job in 1999 after her first disappointment in the turf battles against power lines and she stayed for nine months until the company ceased operations. There she was able to learn about the conflicts between the miners who traditionally worked in the area and the companies that wanted to control the activity.

She later worked at the English Service Corporation Srl, giving English classes to Procter & Gamble workers in the city of Barquisimeto, in the northwestern part of the country.

In 2002, at the age of 29, Lisa settled in Maurak, an indigenous community 30 minutes from Santa Elena de Uairén, at the request of the indigenous people themselves, to manage an Adventist school, but due to her ability to carry out projects and her studies, she was proposed to be captain.

5

Lisa watched through the bus window as they took the wood out of the jungle. It was 1998 and she was coming back to her house for vacation from college. Beyond Tumeremo, where the detour to El Dorado is, wood, a lot of wood, from the Sierra de Imataca Forest Reserve. The trees were huge, ancient. The government was cutting down the jungle.

When Lisa arrived in Inaway (Las Claritas), the place where her family lived and her father worked as an Adventist pastor, the first thing she asked was who was bringing all that down and why nobody said anything. She remembers that someone told her that she had heard something about the removal of power lines.

Lisa immediately went back to 1995 and recalled the arguments of the indigenous leaders who have inspired her, Juvencio Gómez, from Kumarakapay; Alexis Romero, from Maurak; and Silviano Castro, from San Rafael de Kamoirán, and who prevented the construction of the National Tourism Company of the South (Turisur) Hotel Complex, a private project that was endorsed by the National Parks Institute (Inparques), in the Sierra de Lema , mother of all waters and gateway to the Gran Sabana.

—I said we are going to fight because the government had to consult and it didn’t. If they take us to jail for knocking down a stick, we’re not going to allow them to knock this down, they should go to jail too, that’s not the case, they don’t have more rights than we who are from here.

It had happened several times with his uncles and cousins who lived in the Sifontes municipality, one of the most deforested by mining: “Fulanito is in prison for felling a conuco”, “Fulanito is in prison for felling two trees”, “they took away his chainsaw and the captain has to go fight it in the national guard.”

Some authorities said that the government had consulted with the Federation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolívar State (FIEB), which brought together different indigenous organizations of this federal entity and was led mainly by the Pemon people; but Lisa insisted that she should be with the whole town and the captains of the communities agreed with this argument. On July 27, 1998, they left Inaway and blocked the national highway at half past four in the morning.

-I remember that we went into the jungle and found a huge trunk, I don’t know how many meters it was, I couldn’t even count the rings of the tree, it must have been more than a thousand years old and that caught my attention. I was with my cousin Dibisay, who was a captain, and I told her we are going to lower that trunk and block the road. So we went back and started talking to the boys, look at the trunk, we are going to push it and we were the little bunch of men, young people, women, the crowd was large, and it began to roll to roll to roll, the trunk came out of the jungle, we passed by the soccer fields and we put it in the middle of the highway, at kilometer 16, and everyone came and there was no way to move that trunk.

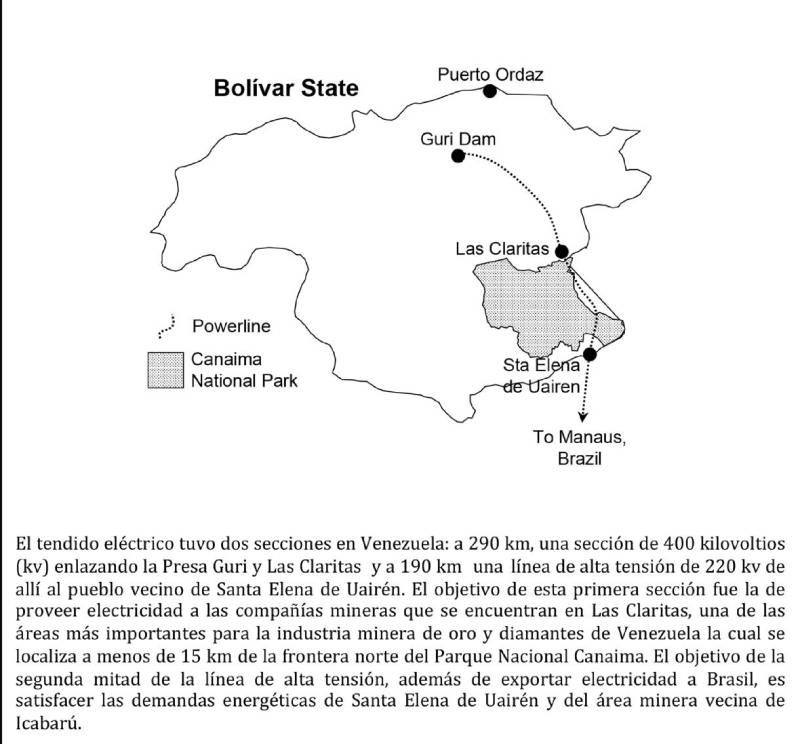

It was a frontal protest against the construction of the high-voltage power line, a project that would take this service from the Raúl Leoni Hydroelectric Power Plant (renamed Simón Bolívar in 2006), located in the Guri Dam in Bolívar state, to Brazil.

Trayectoria del tendido eléctrico. Foto extraída del libro La Conquista del Sur. Vladimir Aguilar y Iokiñe Rodríguez.

In addition to exporting electricity to Brazil, supporters of power lines sought to encourage the expansion of extractive activities in southern Venezuela. providing electricity to the mining companies that were in Las Claritas, one of the most important areas for the gold and diamond mining industry in the country, located 15 kilometers from the northern border of the Canaima National Park. Similarly, they insisted that the energy demands of Santa Elena de Uairén, capital of the Gran Sabana municipality, and the neighboring Ikabarú mining area would be met.

Inaway was one of the first indigenous communities to protest. More would be added. They even had support from Zulia state, at the other end of the country; and even the indigenous people of Amazonas sent them a bundle of casabe (bread made from cassava flour). There was a lot of solidarity. Organizations such as Friends of the Gran Sabana and Survival International spoke out. There were also a lot of people who, as Lisa puts it, “wanted to fish in rough waters.” During the protest, the young people organized themselves and took turns guard duty.

—An uncle who had been in the military told us that now the government wasn’t doing anything, but that at any moment it was going to get upset and they would throw tear gas at us. “They can shoot us, we have to be very careful.” He taught me how far into the ground the flue reached and what to use when that bomb touched you. You couldn’t wash your face, because that burning was disturbing, you had to have vinegar with a handkerchief to be able to counteract that.

His uncle also told him that they should be very careful with infiltrators.

—Twenty-four days we were there, at the level of kilometer 16, they fired at the army, they fired a whale at us— recalls Lisa— The military could only remove the trunk with a tank.

The indigenous people also began to protest against the illegal presidential decree (Decree of 1850) that converted 38% (1.4 million hectares) of the Imataca Forest Reserve, from forest administration, into an area for mining extraction. This decree had been issued a month before the power line project was signed. Both under the management of President Rafael Caldera.

Also in 1998, the National Institute of Parks (Inparques) authorized the German artist, Wolfgang von Schwarzenfeld, to extract the Kueka stone, a 12-meter, 30-ton rock with great spiritual value for the Pemon people.

The dispossession came from all sides.

The struggle lasted until 2001. Lisa continued to form, while she listened to the indigenous people she realized that what the elders were defending was their territory, the bachacos, the birds, the water. “You did the Guri without consulting, you killed many animals. You made the road without consulting…”, said an old man. There was a grandmother from San Juan de Kamoirán who impressed her a lot.

She — she spoke only Pemon and made some speeches. “My territory,” said the grandmother, “I don’t want some guards who come to tell me ‘your ID’, I’m the one who has to tell them ‘your ID’, ‘your ID’, you don’t tell me.”

But at the same time, the young leader noticed the division, the betrayal, the arguments that she describes as “idiotic.”

—One day a general said “but why don’t they want the power line?, if when they have it they will be able to drink cold water”. And for God’s sake, what’s wrong with these people? How are we going to cut down the entire jungle because the Indians want cold water?

The media and the government began to build an opinion matrix that accused the indigenous people of having connections with the Mexican Zapatistas, the Colombian guerrillas, and the CIA, the central intelligence agency of the United States government, which supposedly had borrowed high technology to bring down the towers.

—And I said, well, what happens to these people? Do they think that we don’t think? I remember that there was a strong division in sector 5 of the Pemon people. They continued the fight, knocked down the power line towers, were attacked and militarized. There is always a group more radical than another and they are right. When one has a cause, you die for that cause.

Pemon protests against power lines and Decree 1850 in Caracas 1998. Kumarakapay Photographic Archive.

Meeting of the Minister of the Environment in Gran Sabana. Photo: Iokiñe Rodríguez.

Demolished tower. Photo: Iokiñe Rodríguez.

The situation created a lot of friction between the inhabitants of the communities. One day a soldier from the army, married to an indigenous woman from San José de Kamoirán, fought with a boy who was at the protest and shot him. The young man died. Before they knocked down the towers, the indigenous people grabbed an army major, poured chili on him and put him in the sun. Another day “they plummeted clean” in Mapaurí.

—We remain as I am now with the Bolivarian National Guard, that after they killed my people I can’t stand them, I don’t want to listen to them, I don’t want to see them.

The Pemon indigenous people fought but Lisa realized that the power line project was going to be carried out even if the newly appointed president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez Frías, had promised them when he was a candidate that he would not do it.

The project was part of a long-standing development plan dating back to the 1970s, known as the “Conquest of the South” (CODESUR), and which with the economic crisis of 1994 was revived as the “Project for Sustainable Development del Sur” (PRODESSUR), which instead of showing concern for the long-term availability of natural resources and the integrity of the environment, assumed that the economic potential of southern Bolívar had not been developed and that the large area that remained in a “pristine” state was a sign of neglect and underdevelopment.

—It was fighting against a monster with a thousand heads, you killed one head and another came out. I saw how they play with people, how they criminalize. The government is going to use everything against a people that is fighting for a just cause. So, I dare to say that in cases like this, the government always wins. They start to co-opt. They hire people, they exploit one’s position. At that time they began to buy the indigenous captains, they took them to meetings in Caracas so that they would say “yes, we agree”.

On July 21, 2000, the five points of understanding -which were originally seven- were signed between the National Executive and the FIEB. A fraction of Sector 5 of the Pemon people considered this a betrayal of their struggle and a lack of respect for their decision-making processes. In one of the points of the agreement, the National Assembly was asked to approve Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. It was the only thing they did.

—In everything else they danced us. They said that all the communities were going to have electricity. That’s a lie. Not all communities have electricity. For example, Maurak has a debt, but when I was captain I said that I was not going to pay that because now I have 38 towers and a substation in my territory. There I decided to learn the law because they will always treat us as if we didn’t think, crazy people who are being ordered by other people, so, definitely we have to study. Indigenous peoples have the right to decide and participate in the administration and use of the natural resources existing in our territories.

A short time later, a Pemon group from sector 5 resumed political action against the power lines and renewed their claim in a debate about the desired development model for southern Bolívar. The government publicly said that the impact of the power lines was minimal, and that the opposition was reduced to a small group of radical Pemon leaders. Later, when seven poles with power lines were knocked down in the Gran Sabana, the area was militarized to later finish the project. The power line was inaugurated on August 13, 2001.

In his book Games of Power in the Conquest of the South. Domination, resistance and transformation in the fight against extractivism (2021), Iokiñe Rodríguez and Vladimir Aguilar write that the power line conflict had a great cost for the Pemon of the Canaima National Park, since it ended up fragmenting their organizational and leadership structure, severely crushing the morale of those who consistently opposed the project. “A leader, who eventually became the first Pemon mayor of the Gran Sabana, refers to this episode in his life as ‘the trauma of the power lines. At the same time, the new legal framework created a scenario to advance the indigenous rights agenda. So they continued to work with the state, even though they were fragmented and demoralized.”

The laws that the government passed provided a more specific legal framework for the protection of indigenous political and cultural rights. This included the 2001 Law for the Demarcation and Guarantee of the Habitats and Lands of Indigenous Peoples, which was followed in 2005 by the Organic Law of Indigenous Peoples and Communities (LOPCI 2005). Additionally, at the international level, Venezuela ratified in 2001 the ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, and in 2007 the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous Peoples.

“In 2002, and in collaboration with a series of NGOs and universities, the Pemon began a series of territorial self-demarcation processes in different sectors of the Canaima National Park, in preparation for the official land demarcation and titling process, which would begin in 2005. Likewise, the Pemon took important steps to try to position an alternative narrative of development in the space of public policy, based on the experience of the Kumarakapay community in 1999, when they developed the Life Plan of the community”, the researchers point out.

However, the process of territorial demarcation and titling turned out to be slow, complicated, and inoperative for the majority of the indigenous peoples, including the Pemon, especially because a logic of security and geopolitical integrity prevails from the government, based on the control and militarization of these peoples. territories rich in gold and other minerals for exploitation. According to their reasoning, granting indigenous peoples legal possession of their territories would constitute a threat.

Being a Pemon is based on a relationship of respect towards the spirits and beings with whom they live in the territory. Photos: Minerva Vitti.

Twenty years after the new constitution and the absence of the demarcation, Vladimir Aguilar considers that it is important to continue demanding the demarcation and titling of territories, but from the perspective of self-demarcation: “I believe that these are times of empowerment of rights, consequently The struggle for land and the claim for territories must start from the empowerment of the indigenous organizations and special jurisdictions, which are in the traditional institutions and in the forms of organization that the indigenous peoples and communities have in an ancestral way and that today they are an instance of resistance and resilience. I believe that the process now goes from the bottom up, that is, nothing can be expected from the State, but rather it has to be born and exercised from the communities and the State is obliged to recognize it. That has to go through a process of intercultural dialogue, it has to be mainstreamed by interculturality and multiculturalism, as recognized in the preamble of the Constitution and it is a way of strengthening the democratic experiment in our country”.

This is an excerpt from the complete profile on the life of Lisa Henrito, published in SIC magazine in September 2021.

This report was originally published in Revista SIC on September 18, 2021, as part of the “Women Defending their territory” project of Climate Tracker and FES Transformación.

Leave a Reply