Andalgalá: the voice of the Algarrobo – Chronicle of a fight without legs but that walks

JUANA MALDONADO

(ARGENTINA)

Standing outside the police station, Rosita yelled a phrase at the top of her lungs that would be indelibly etched in the history of the struggle: “Why do those scoundrels who sit behind their desks drinking coffee, deciding what we need for Andalgalá, put us in these types of situations? Why have we had to walk here every Saturday for the past eleven years without ever being listened to? Even the priest was lobbying for the mining company! Why do we have to live like this? But we are not tired. If you think that because they frightened us in 2010 and imprisoned our comrades we are going to give up, you’ve got another think coming. It is either the mining company or us. There are no two ways about it.”

It was April 2021 and 12 of Rosita’s colleagues were at the police station, under arrest for demonstrating against the Canadian mining company Yamana Gold that has set up business in the territory.

Rosa Farías is 58 years old, measures four foot nine at most, and is stocky, with a dusky complexion and shoulder length, curly brown hair. It is one of the paradoxes of life that this retired teacher who has been fighting since ’98 has osteoarthritis. She can barely walk and has spent Saturdays at home for some time.

Rosita’s knees are stiffer and more swollen than before, and she knows she won’t be able to keep up with the others. But it is 5 o’clock in the afternoon on August 7 and she is sitting on a bench in Plaza 9 de Julio opposite the pink church of St. Francis of Assisi. The 600th Walk for Life organized in Andalgalá, a city in the province of Catamarca, in northwestern Argentina, is about to start.

The El Algarrobo Assembly is responsible for staging the resistance against mega-mining in the territory and the defense of water. For the past 600 weeks, they have been walking every Saturday to demand a stop to the activities on Mount Aconquija.

I think every moment I survived walking

And every second of uncertainty

Every moment of not knowing

They are the exact key to this fabric

That I’m carrying under my skin

So, I protect you, here you are still inside

Amid the sound of Natalia Lafourcade’s “Hasta la raiz” and the carnival music being played, a handful of children run around and write “Water for life,” “Don’t explode the hill” on bits of colored paper. Smiles are visible despite the facemasks: it is a protest, but it feels like a celebration. ”Grab a poster, that’s what they are here for,” says someone with the microphone, pointing to the banners displayed on the floor: “Water is worth more than gold,” “Mega-mining without a social license,” “Genocidal governments.”

“The number 600 makes us happy because it means that our people are still alive, but it is also makes us sad because we have spent years not being listened to. This is no longer a participatory democracy,” Rosa explains, surprisingly calmly.

Rosa Farías

The snow that makes up my mountains

The National Glacier Act prohibits “the release, dispersal or disposal of polluting substances or elements” on glacier surfaces or periglacial environments, an area with frozen soils that acts as a water regulator. According to the Argentine Institute of Snow Science, Glaciology and Environmental Sciences (IANIGLA), there are ice sheets only 700 meters from the mining settlement in Andalgalá, located in a periglacial zone. In March, the Ministry of the Environment confirmed the information based on an audit.

A month later, bulldozers climbed Mount Aconquija.

They did it on April 7, through a neighboring department, in secret. MARA (Agua Rica-Alumbrera Mine) is the result of the merger between two previous mines and their respective infrastructures. The consortium, together with Glencore and Newmont Goldcorp, is at the advanced exploration stage: they expect to achieve annual production of 533 million pounds of copper, 107 thousand ounces of gold and “contributions” of molybdenum and silver in the first 10 years. The mine would have a useful life of 28 years.

The fact that there are machines on the mountain grieves the people involved in the struggle. As a result of the news, the massive, peaceful invitation to walk N°583 on April 10 ended with a suspicious fire in a warehouse belonging to the company. The place was completely destroyed. In the search for culprits, 12 assembly members were arrested.

The deposit is located in the center of the Minas River channel, which together with the Blanco and Candado rivers forms the Andalgalá River basin, used for the irrigation, energy and human consumption of that city and its surroundings. The water is snowmelt from the glacial layer and periglacial environment covering the mountain range.

Open pit mining would mean that explosions would produce greenhouse gases and dust. The mineral dust that could be scattered is sulfides. If that mixes with rainwater, it releases a stream of sulfuric acid, which is highly reactive and attacks rocks,” explains the Andalgala geologist from the University of San Juan, Aldo Banchig.

“Sulfur is still present in one of the mining areas of the hill, and when it mixes with surface water, it produces a turquoise-colored stream, which is copper sulfate,” Banchig reports. He also notes that, for now, the river is “pretty good” in terms of drinkability.

One of the achievements of the Assembly was a judicial ruling by the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation. In 2016, it determined that the activity of the Agua Rica mining company was damaging the environment and society, and warned of avalanches, landslides, water contamination and health repercussions, as outlined in the General Environmental Act.

Based on the court ruling, that same year the Municipality of Andalgalá unanimously approved Ordinance 029/2016 prohibiting mining activity. The rule was repealed in December 2020 by the provincial Supreme Court, which declared it unconstitutional. The justification was that since the province does not have an environmental act that prevents mining operations, no rights were being violated, which is why the machines made their way up the hill last April.

The context in which the Escazú Agreement, ratified by Argentina, has been in force since April 22, raises the question about the degree of responsibility of the state when the people defend the territory. The Latin American and Caribbean treaty is designed to guarantee access to information, justice, and citizen participation in environmental issues, as well as the Human Rights of those who defend the territory in the region, the most dangerous one in the world for environmental defenders, according to Global Witness.

“If the state does nothing or is insufficient, it is in breach of the Agreement. You can appeal to the international body to ensure that for judicial decisions are complied with, for example,” says Andrés Nápoli, FARN director and a party in the treaty negotiations.

Fighting is in the air

“This place belongs to everyone,” says José Martiarene when he opened the gate of the El Algarrobo headquarters, the site of the community radio station they founded in the small town of Chaquiago. The door with a photo of Santiago Maldonado opens onto a small study with beautiful murals of the indigenous populations, a plastic table and a couple of microphones. This is where the Assembly denounces the extractivist system that prevails in the world, which is exacerbating global inequality; the famous North-South asymmetry.

With a panoramic view of the mountain range, this humble dirt and sand terrain is dotted with flags representing the struggle. Some serve as strategic walls because they say that a neighbor spies on them to pass on information to the authorities. This is hardly surprising since the headquarters is on the road MARA trucks take to climb the hill and sometimes the Assembly decides to cut it off. Their protests were repressed there on February 15, 2010.

“The Voice of Algarrobo,” the star program is hosted by Rosita Farías on Saturdays from 11 to 13, although the last time “she took a well-deserved vacation,” said José. It is the same reason she does not go on walks. But for more than six years, her voice acted as a conduit between the Assembly and the rest of the people; the adjustment knob that finds the frequency, a form of resistance: The snow-capped mountain Aconquija must not be touched,” says the wall outside.

The headquarters of El Algarrobo, where the community radio station they founded in the town of Chaquiago is located

According to Rosa, “Learning” is what has defined her years of struggle. She is careful with information, even if she does not know whether there are people from the other side listening.

“There is a high level of empowerment and appropriation of legal norms, that the people of Andalgalá have used as tools,” explains the Assembly lawyer, Mariana Katz. “They realized that knowledge is as important as a social expression. People in Andalgalá know that human rights exist and that is not just about the police not beating you.”

Rosa plays an active role in communication, which in recent years has intensified as her legs have got worse. She does not need to leave her home to be an activist and is sometimes so active that many people involved in the struggle say she can sometimes be a real pain in the neck.

She decided to skip the historic Hike 600. There she is in front of the pink church, on the bench closest to the speaker, listening to what her colleagues say, as if to make sure that everything runs smoothly. She realizes this “is not about Rosa.” “For us older people it is a relief to know that there are young people next to us. Not behind us, next to us We stand side by side, holding hands.”

I forgive but I never forget

Nobody could have imagined what was going to happen. The people who felt the clubs continue to feel them on their skin and the blows and screams continue to resonate in their heads. Young and old. Their wrists still bar the mark of the tightly tied rope. And afterwards? The humiliation of having your physical and mental integrity violated, the fear of going out, of losing your job, and of having them go after your family. There was a lot of crying involved; empowerment might come later.

That description could refer to the repression of February 15, 2010, when they beat everyone—everyone—in the Andalgalá world for the first time, or the raids and arrests that began in April 2021, after the fire. The surprise effect, the criminalization of protest and excessive violence, were present in both. At first, Rosa thought the term “mining dictatorship” was a bit of an exaggeration, she admits. But those events made the words come out effortlessly.

“February 15” is a phrase, an idea that has already been etched on the collective imaginary. When José found his partner with their son in her arms and her back shot to ribbons. When Sara Fernández and her mother clung to each other on the ground while they were beaten with sticks and kicked. That day, while the neighbors were singing the national anthem, several others were put into police vans. Even the figure of the Virgin with her white cape was riddled with bullets.

Rosa Farías hosts “La Voz del Algarrobo”, the flagship program of community radio, on Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.

When the situation was repeated in April of this year, Rosa, one of the women most committed to the struggle, did not have the strength to ask about the details of the latest arrests: “I knew I was going to break down. Because they are boys I know, who grew up in the struggle and I regard them as my sons,” she said wistfully.

Rosa, this warning is for you: the following paragraphs detail those events that began on April 12 2021 and may make uncomfortable reading.

Sara had finished an English class when, just after 10:30 am, a group of police officers broke into her house. She asked for an explanation, although she imagined that they would stretch it out for a couple of hours and that would be that. But one of the police woman put her arm around her neck and squeezed until she fainted. As she fell, she hit her head on a piece of furniture. “Don’t be so feeble,” they said laughing. And with Sara finally on the ground, with no oxygen and her hand injured after it had been stomped on, they managed to pull her by the hair and put her in the van.

The residents of Andalgalá say that bad things do not happen in the town. It is usually peaceful and at most they can steal your bike. However, the arrests were made by forces from the Kuntur group, Catamarca’s special division trained to deal with cases involving situations such as hostage-taking, complex raids, and transfers of dangerous prisoners. Is Andalgalá a peaceful town?

Those who demonstrated on the day of the incident have doubts about how things happened; that the door opened very easily, that there was not even one fire extinguisher. The firefighters two blocks away took two hours to arrive and the area was empty of police officers, who always closely monitor the walks, except that day. Nobody knows anything, but 12 people were held in custody for 15 days.

“They chose them so they could interrogate them One of the boys was taken out of his cell at night; they began to say that they knew his son. They asked him if he was not afraid that his pregnant wife was alone, and why he wouldn’t say who had done it. They looked for people who might crack under pressure, but no one saw anything connected to the fire,” said Sara. According to the compilation of various testimonials, the days they spent in the police station (in some cases it was three or four until they completed their sentences under house arrest) they had no sunlight, and were kept in damp, dark cells, with dirty mattresses and toilets without water.

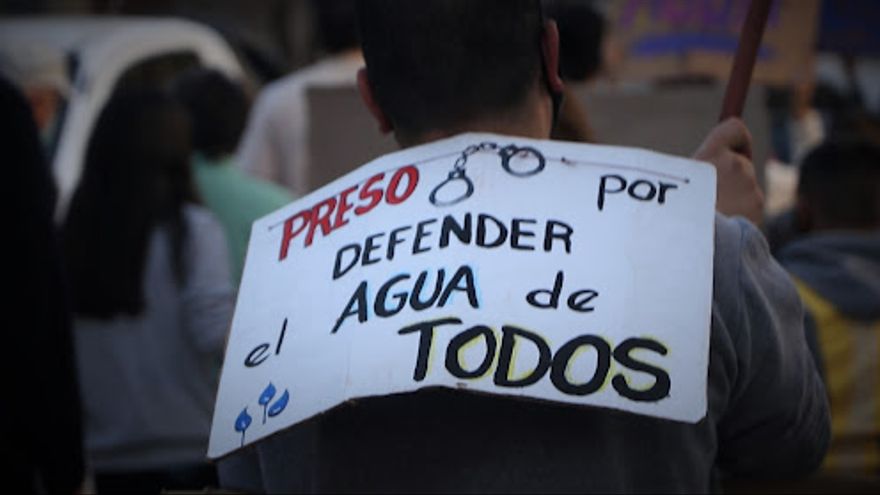

Many of those people are taking part in the 600 race today, still with ongoing legal cases. One of them is carrying a sign that says, “Imprisoned for defending the water that belongs to everyone.” Some are still afraid and choose not to join the march. This is where Aldo Flores comes in and says that marching is for the military, that Andalgalá walks, it does not march.

One of the detainees in Andalgalá, on a walk through life

During those days of anguish at the police station, there was always a group of people camped outside that foreshadowed hope. It was El Algarrobo, relatives and people who had come of their own accord and made a noise to demand the release of their companions. Although one of the detainees said that on the inside, it was impossible to make out what they were saying, he found the noise reassuring. Outside, Rosa yelled with all her might, telling him to stay calm and that his family was fine, because they had just tested positive for Covid-19. Although he could not understand what was being said, to him the words felt like the sun he had not yet been able to feel in the cell. Or like a mother’s hug telling you that we’re going to get through this.

José said that with five more women like Rosita, “We would have got the Falkland Islands back.”

We are showing the way

Despite the sleepless nights because of her anxiety, the afternoons she couldn’t breathe because of the tear gas and the street demonstrations in Buenos Aires that made her knees even worse, Rosi is laughing from her bench in the plaza. You cannot carry on a conversation with her without her being interrupted to greet someone with a hug. She will be on tenterhooks until the walk returns to the starting point. Her daughters and grandchildren will walk on behalf of her: “You are going to be the voice and we are going to be your body,” they told her a while ago, because the struggle is the last thing you give up.

The softspoken speaker’s greetings for the Assembly can be heard through the loudspeaker. It is Nora Cortiñas, “Mama Norita” as she is known here. The Plaza de Mayo Mother always rooted for Andalgalá, although she defines herself as “supportive” of the demands. The Assembly says that she opened many doors for them. In the village, her name is sacred.

“State terrorism did not develop of its own accord,” explained Nora, “It was created to implement an economic model to suit the United States. Argentina is a country that is not poor; it is impoverished because it has a crushing debt. So now we are mounting a huge resistance because the people were repressed, tortured and the extractivism trucks continue up the mountain removing our wealth to give it away.”

The 91-year-old woman knows exactly what walking represents. Her footsteps began to create paths in 1977, when the walks around the Plaza de Mayo marked the beginning of a revolution in the midst of a military dictatorship. Norita knows more than anyone what it means to confront economic power, an entire system that scorns life and tries to silence the voice of the peoples. It is no coincidence that walks through life are precisely that: walks. You clear a path to bring to light what is hidden and anomalous, a legacy of the Mothers that El Algarrobo used to build a present with memory and a future with hope.

The sociologist Horacio Machado Aráoz says that “the expropriation processes that began with the brutal violation of “human rights” in the military dictatorships of the 1970s continue today. Nowadays they take the form of ‘the degradation of bodily materiality that makes ‘individuals’ and populations’ corporealities that can be acknowledged as the ‘legitimate bearers of rights’”. Historically, the natural wealth of impoverished countries was plundered to serve the richest people, meaning that today, even in democracy, systematic extermination plans are indirectly implemented against the population.

Andalgalá walks in defense of water

“Andalgalá does not forget the repressions, the ridiculous prosecution merely for defending the water,” reads Ana Chayle, a slight woman holding the microphone in the square just before the start of the 600 walk. “It seems that political power does not exercise its memory. That is why it does not realize that every time they touch one, a hundred more go out into the street. That is why they did not understand that Andalgalá gets back up again and is strengthened after every onslaught.”

The people have swollen legs from so much walking. Each step becomes more difficult because the path is steep and rocky. Their destination is the source of the river; life. The time Andalgalá has spent walking is embodied every day, in every tear and in every laugh, because it knows that peace and quiet do not last long. But that gloomy conviction makes it more resistant to each blow and collectively strengthened. There are no proper names, no individuality. It is the love of the territory, history, and the future; memory and hope that feed each other, because one exists because of the other, just like companions in the struggle for their lives, yours, and mine.

Andalgalá does not rest but it has a clear conscience and so it walked the streets that August 7 for the 600th time but it also continued and will continue to take part in the 601st, 602nd and 603rd walks. Self-determination powers its legs that have a thousand problems, yet nonetheless manage to walk.

This report is part of the Defenders of the Territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformacion.

Leave a Reply