A daughter of the Earth, Edel Moraes is the voice of extractive peoples

Jessica brasil skroch

(brasil)

The defender from Marajó fights for the right to the territory as a place for the reproduction of life. In Marajó, the people and the land are one.

“One day I just want to highlight the beauties of my Marajó. And say how many good people there are who conserve, preserve, and protect the environment. The landscape is beautiful, the forest is generous, the earth is the mother, water is life. However, in the midst of that wealth, we have the lowest human development indices in Brazil. It is a territory that is undergoing an orchestrated, historical process of epistemicide, the death of the rainforest and native peoples.”

“What is the relationship between the lack of water in the city and the Amazon, and traditional peoples and communities? Few people will reflect on that. The majority will remain indifferent to these issues and believe that the indigenous peoples who are fighting against the time frame are only a problem for the indigenous people themselves. We do not know our own history. People are unaware of our connection with nature. In any issue concerning climate change, indigenous territories are the last frontiers of the planet’s equilibrium. Without the forest, the world’s climate will collapse.”

At the age of nine, Edel Moraes was forced to leave her community, her family, and her land in the Marajó archipelago, in the Amazon region of northern Brazil, to work and study in the city. Being born in Marajó, a mestizo and the daughter of extractivists, practically condemned her to have her rights violated, as if she were not a person. Sadly, she understood this at an early age. After twenty years of struggle in defense of the traditional peoples and territories of Brazil, she is a tireless voice that advocates for the recognition of what should be obvious: “The rainforest is inhabited by people.”

Leaving home as a child was not a choice, nor was joining the struggle. Edel does not see herself as an activist because, for her, being an activist was not a decision, but a question of survival. “The forest is not a cause: it is our life. We are part of it.” Defending the conservation of the forest means defending the people who live in it. Instead of referring to the environment, she speaks of the “whole environment,” in which people and territory form a whole.

“We are not invisible, but they make us invisible,” she repeats in every denunciation she makes. Whether at university, a public hearing, or international forums, such as the Climate Summit, Edel carries the message that rainforest peoples live, conserve, and protect the environment, thereby providing a service to all of humanity. However, their lives are constantly under threat, especially because of the “dismantling of public environmental policies implemented by the government itself,” she warns. The “Adopt a park” program, involving the donations of goods and services by companies and individuals for Conservation Units, is an example of this.

Edel participates on so many fronts that there would not be enough room to list them in this text. Among other things, she is vice president of the Chico Mendes Memorial, an organization affiliated to the National Council of Extractivist Populations (previously known as the National Rubber Tappers’ Council, (Portuguese acronym CNS), of which she was also vice president. She still participates in the Group of Dialogic Studies and Practices in the Context of Traditional Peoples and Communities, at the University of Brasilia.

In the cradle of the acai harvesters

The Pagão river was the birthplace of a forest guardian. Edel was a happy child in the community of Boa Esperança, in a town devoted to agriculture in the municipality of Curralinho, in the Marajó archipelago, between the states of Pará and Amapá. From Belém, the capital of Pará, it takes about three hours by boat to Marajó, depending on where you disembark. Edel’s rural community is an hour and a half’s drive from the urban area of Curralinho.

The days spent in the company of her parents, eating what nature produces on the banks of the river, were replaced by engaging in domestic labor to pay for her studies. “In the place where I was born, education was only available up to fourth grade. From then on, if you wanted your child to study, they had to leave the community,” she says. In family homes, childhood dolls were the children of other parents.

With the understanding she now has, Edel realizes she was a domestic slave. There was no respite from the pain of child labor, because being far away from your home and family aggravates any difficulty, particularly so for a child. The little girl could not bear to live away from home and went back to her parents and the rainforest. However, with no other option, at age of 11 she returned to the city, where she remained until she became an adult.

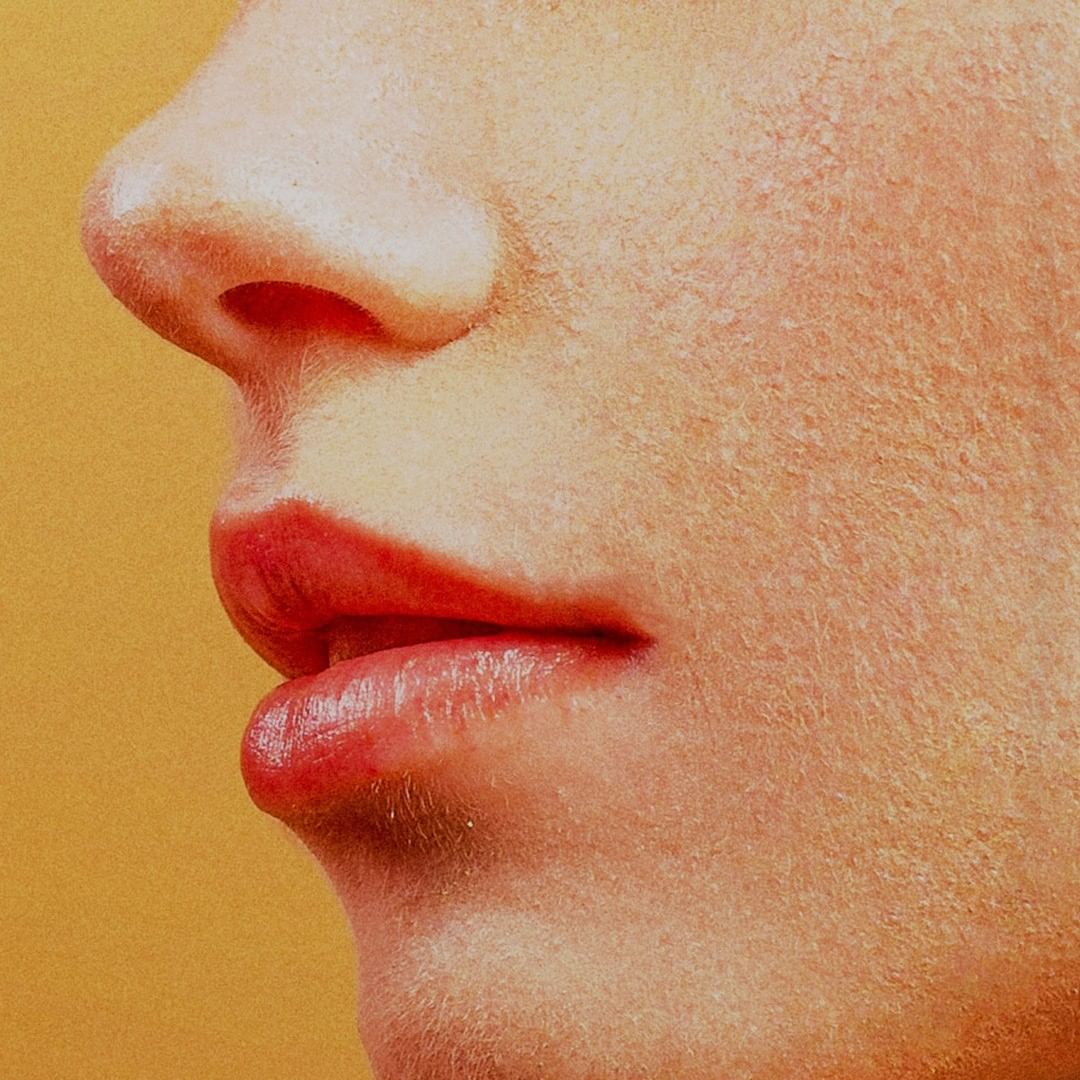

Photo: Caroline Torres

In the brief time she spent in Marajó, lullabies had turned into the cries of the struggle she would assume for a lifetime. “I fell asleep to the sound of ‘Come on, come on, waiting is not knowing,” she recalls while reciting the words of the song “Don’t say that I didn’t talk about flowers” by Geraldo Vandré. Her parents, Miracélia Moraes and Dulcimar Moraes, were involved in the grassroots ecclesiastical communities and the Rural Workers’ Union and took part in the agrarian regularization movements. Her mother, her role model, was one of the first leaders of Pastoral Care of Children in the territory and took part in the first Marches of the Daisies, a demonstration by Brazilian rural workers.

Like father, like son. The seeds of the defense of the earth, equality and nature grew in Edel’s heart. After completing her secondary education, she returned to her community at the age of twenty, wanting to do justice. “With my eyes blazing,” as she says, she began to fight to ensure that no other child from Marajó would have to endure the abuse she suffered.

The flowers of what has been sown

Shortly after her return in 2001, Edel was elected to the first Guardianship Council of her municipality and participated in efforts to guarantee the rights of children and adolescents. Since then, she has taken part in various projects, movements, and social organizations of extractive communities. After over two decades of experience, not even she can remember everything.

She fulfilled her dream of being the first person in her family to go to university, where she studied pedagogy. Later on, she completed a specialization course in Rural Education, Development and Sustainability and a master’s in sustainable development in traditional towns and territories.

Access to education marked a turning point in Edel’s life, and she wanted to give the people of Marajó the same opportunity. To change the reality of the high illiteracy rates in her municipality, Edel voluntarily coordinated a project with more than forty literacy courses for youth and adults. This project led to the youth and adult literacy movement “Mova Pará Alfabetizado” (Agitate for a Literate Pará), a program run by Pará state government.

Under Edel’s pedagogical supervision, the movement has reached the entire Marajó archipelago, where 22% of the population over the age of 15 is illiterate, whereas the rate for Brazil is 9.6%, according to the latest census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), published in 2010.

“I may not make money from most of the work I do, but my reward is achievement. When people stop violating a child’s rights. When an adult learns to read and write and asks for a new identity document in which he can sign his name,” explains the activist, with a catch in her voice.

For a collective territory

Photo: Caroline Torres

It is hard enough to work out how Edel’s day fits into just 24 hours, but matters are complicated even further when challenges come into the equation. “This is a rich territory from the point of view of socio-biodiversity, but a poor one from an economic point of view. That doesn’t add up,” she says.

Of the sixteen municipalities comprising the Marajó Archipelago, 14 have a low or very low Human Development Index (HDI), according to the Brazilian Human Development Atlas. Communities have poor basic sanitation and ineffective water treatment, which is a cause of disease in the region. Moreover, not all localities have electricity, telephone, or Internet access. Edel’s community, for example, was only electrified about two years ago, as a result of popular pressure, which managed to disconnect the power lines of the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant, which passed over the houses but did not reach them.

In the midst of so many difficulties, Marajó has a solid history of organizing and social mobilization, of which CNS is the main reflection. The council, which was founded in 1985 by a group of rubber tappers, including Chico Mendes, a prominent Brazilian environmentalist, fought against the devastation of the rainforest and the expulsion of extractivist populations from their lands in the Amazon. The result was the recognition of the Extractivist Reserves (Resex), in 1990, as territories throughout Brazil, which protect the livelihoods and culture of extractivist populations, who make their livelihood from the sustainable use and management of natural resources.

“The river is a means of transport as well as a source of food. In addition to their fruits, trees give us our demarcation references. We are defending a territory that is not just a piece of land, but a territory in which we exercise our way of life, ancestry and spirituality, dimensions that go beyond what can be measured,” explains Edel.

In addition to her educational work, Edel has always participated in debates on the regularization of land tenure. She was a speaker at the public hearing for the creation of the Terra Grande – Pracuúba Resex, in Curralinho, in the state of Pará, a victory against the companies that had threatened to evict residents from the territory.

As a result of her participation in the extractivist movement, Edel was the first female vice president of the CNS in over three decades of history. When she visited Chico Mendes’ home in Xapuri, Acre state, she felt the energy that confirmed that she was part of the rubber tapper’s legacy. I said to him: “Friend, if you are in another dimension, you can rest easy, because here you are still very much alive. I will continue to be an instrument of your voice and your struggle, which is also that of many people,” she said.

A daughter who is also a mother

Her activities meant that Edel had to spend a lot of time outside her territory. In the city, she realized she was a woman from the Amazon. She became increasingly aware that her identity was tied to the territory she had left. Edel was a daughter, but also a mother of the forest.

“We are not orphans who need to be adopted. We are children of the earth, children of the forest,” declared Edel at the first meeting of the Convention of Belém do Pará Group on the Adopt a Park program, launched by the Ministry of the Environment in February this year. They are auctioning the land with us inside, without even asking us,” she told the attendees, who are part of a network for the defense of social and environmental rights.

Decades of achievements are now being threatened by the collective dismantling of environmental policies, says Edel. Among the threats is the Adopt a Park program, which encourages the donation of goods and services to the Amazon Conservation Units (UC) by companies or individuals. The initiative is framed as a solution to the lack of funding of the UC managing body, the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio). In 2021, the government of President Jair Bolsonaro slashed ICMBio’s budget by 24.4% in comparison with 2019.

During the first phase of the program, 132 Conservation Units will be considered, including 50 Resex. In exchange for donations, companies will be able to put up a signpost in the area with their logo, indicate in advertisements that they are members of the adopted Conservation Unit, use the territory for temporary institutional activities, and be included in the management plan.

“There is no provision authorizing the Ministry of the Environment to use the area without the authorization of the concessionaire and the UC Deliberative Council for purposes not foreseen in the respective management plan,” says Edel.

Photo: Caroline Torres

According to the movements opposing the program, there have been several violations of the rules and regulations. Edel points out that the measure does not respect the guidelines of the National System of Conservation Units or Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, stating that all traditional peoples must be consulted, in a free, informed fashion, before decisions that may affect their property or rights are made.

Edel believes that the program threatens the autonomy of communities in the interests of “greenwashing,” whereby companies project an image that they are concerned about sustainability, but do not change their production methods that impact the environment. No territory has officially been adopted to date, but there are already eight protocols of intent from major international companies such as Carrefour, Coca-Cola, and Heineken, interested in the Lago do Cuniá Resex (Rondônia) in the Javari-Buriti Relevant Ecological Area of Interest (Amazon) and the Quilombo do Frechal Resex (Maranhão) respectively.

The lack of transparency of the program has also been criticized. The protocols of intent signed by the interested companies were not published by the MMA, “which constitutes a violation of the principle of transparency of public administration,” explains Pedro Martins, legal advisor for Tierra de Derechos. Moreover, the decree fails to clarify what goods and services private enterprise may transfer, while the work plans of the interested companies have not yet been made public, says Suely Araújo, specialist in public policies at the Climate Observatory and former president of Ibama (Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources).

The situation is even more serious because it is happening in the middle of the pandemic, adds Edel. Communities have little or no access to telephone and Internet signals, which are the means of resistance during the pandemic. We were able to contact Edel for this report because she was in Belém, the capital of Pará. “They are trying to push things through at a time when we can’t react,” she complains.

[Careful!] “The adopting company is actually renting the territory. Traditional communities are simply being ignored. Can you imagine if I turned up and said that from now on your house was no longer yours and that I would set the rules? These are new forms of epistemicide, a type of destruction that began with the invasion of Brazil and is now continuing institutionally. These are our last spaces of resistance and existence.”

The “Adopt a Park” program is part of a context that reveals this government’s lack of interest in the environment and traditional communities, to the detriment of policies that generate benefits, experts say. The first two years of the Bolsonaro administration saw the worst devastation of protected areas in the Amazon since 2008, according to a study by the Socioenvironmental Institute using data from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). At the same time, 2.9 billion reais from the Amazon Fund for preservation actions have been frozen since April 2019, after Brazil changed the fund’s management structure without consulting Norway or Germany, donor countries of the project.

Moreover, in April 2021, the Regional Agreement on access to information, public participation, and access to justice in environmental matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the Escazú Agreement, came into force, but Brazil did not sign it. “The Bolsonaro government is planning to destroy forty years of public environmental policies,” warns Araújo.

Edel is human too

“It is difficult to get away from rainforest time. In the stone forest (the city), life is complicated. I miss the time I didn’t spend there because of all my comings and goings,” Edel admits. Once, after three months of traveling through the north of Brazil, she heard a person from Marajó who was envious of her life and travels. At that time, when I arrived in Belém, I had no money to go home. I stayed there for two days, until I got a loan,” she says. Deep down, sometimes she just wanted to be home with her family.

In her mission to guarantee the well-being of the next generations of traditional peoples, Edel says she has always experienced a “populated solitude.” My son became a man, and I didn’t even see him grow up. You pay a high price for the fight. Her personal history combines with a collective history, for which she feels responsible. “But I am also a woman; I want a husband; I want a child. You have to learn to balance all that.” Edel is human too

[CAREFUL] “At first I thought I was fighting to save the rubber trees. Then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest. Now I realize I am fighting for humanity.” Chico Mendes

It has never been a matter of choice. Like Chico Mendes, Edel knows she is not just fighting for her own rights: Brazilian society has failed to understand that it is responsible for the territories, that it is not going to defend traditional communities and peoples, but that it is going to defend itself. The idea that society is separate, that the country and the city are unrelated, is completely mistaken.

This report is part of the Defenders of the Territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformacion.

Leave a Reply