Germinda Casupá, an indigenous Chiquitana woman fighting fire

ESTHER MAMANI

(BOLIVIA)

The fires that caused havoc in the Bolivian Chiquitania—the largest dry forest in the world—left dead animals and damaged trees and plants in their wake and affected indigenous families. In response to this catastrophe, indigenous women assumed the defense of their habitat.

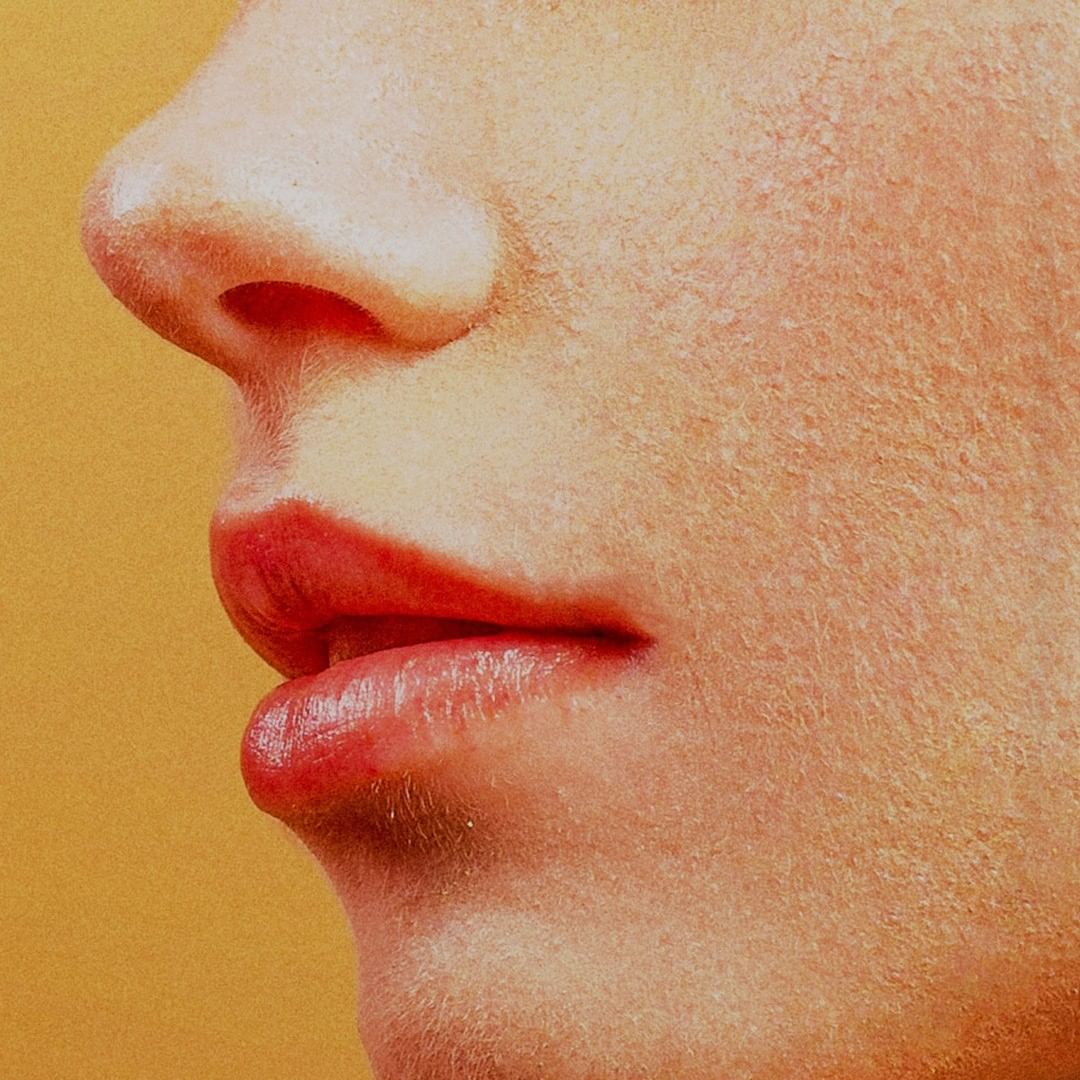

“The fire was advancing quickly, and we fled to the farms to avoid the flames. We fetched water in drums for a fortnight, as we watched our animals die; the fiercest ones ran straight past us as they burned,” said Germinda Casupá Parabá, an indigenous Chiquitana woman. She took a deep breath before continuing to tell her story to the judges of the International Court of Nature, in Chile.

On December 18, 2019, her confident voice failed to hide the sadness of remembering that five million animals had died in the fires that devastated over six million hectares in the forests of Chiquitania in Chaco and the Bolivian Amazonia that year.

The Bolivian Plurinational State, denounced by the National Confederation of Indigenous Women, responded with silence. No representative of the Ministries of the Environment or the Presidency was in the room.

The leader introduced herself as vice president of the Organization of Indigenous Chiquitana Women (OMICH) and the ruling would also determine her leadership in the communities of the municipality of San Ignacio de Velasco, Santa Cruz, in the middle of Chiquitania.

Germinda Casupá in an interview for the medium “Muy Waso”. Photography: Esther Mamani

During the seven minutes of her presentation, the leader took several sips of water from a glass on the lectern; her anger and helplessness were palpable. This was hardly surprising, since the forests, where she used to play as a child, the habitat of hundreds of indigenous families, had turned from green to grey and were impregnated with the smell of ash.

Arriving at that moment had involved weeks of preparation, reading, and reviewing testimonials in which she was accompanied by various indigenous groups and environmental civil society institutions.

Images of trees turned to ash, indigenous families on the highway, wild animals in places where they had not been seen before, and other wounded mammals were part of the evidence presented and compiled by the Bolivian College of Biologists.

All this and Germinda’s story shocked the jury. Accordingly, in August 2020, the Court of Nature ruled that former president Evo Morales (2006-2019), the then interim president, Jeanine Áñez; provincial government authorities of Santa Cruz and Beni; those responsible for the administration and control of lands and forests; justice operators; national assembly members and agricultural and livestock businesspeople were guilty of the crime of ecocide.

The Court detailed the victims of the ecocide: wild animals such as the maned wolf, jaguar, blue and yellow macaw, tapir, swamp deer, otter, peccary, alligator, parrots, capybara, anaconda, guanaco, pampas deer, black howler, fallow deer, and rhea. In addition, over six thousand plants, many of them endemic, had been affected.

Chiquitania, the Bolivian pearl

Dirt and gravel route between San Ignacio de Velasco and Santa Anita. Photography: Esther Mamani

A year after the ruling, during which the Bolivian State has not followed any of the Court’s recommendations, Germinda understands that power shields those responsible with impunity, although she has not lost hope that at some point compensation will be paid for the damage caused.

The ruling was a victory, but also the beginning of more work, because the fire returned to Chiquitania in 2021 even more forcefully. The new fires require Germinda to continue to douse the flames.

The indigenous leader is now visiting communities to review the actions being implemented. Monitoring involves updating the number of families per community, and checking whether they have drinking water, vehicles are available, and they have gasoline for possible evacuations.

It is six o’clock in the morning on the last Friday of July 2021 and Germinda has a proactive, dynamic attitude expressed in this new scenario. She is witty and quick to respond, which makes conversations on such thorny issues as heat spots more bearable.

Chiquitania is the largest tropical dry forest in the world and, until 2019, the best preserved. Most of it is in Santa Cruz. Despite the studies conducted, barely twenty percent of its biodiversity is known.

The destruction by burning of the plant biomass affects the structure of the forest and the production of seeds for new trees, as well as the water cycles, since when soil cover is reduced, less rainfall occurs due to the reduction of infiltration.

“We will have to make the transition from concern to action,” says Germinda firmly, before getting into the taxi we hired to visit three communities in San Ignacio de Velasco: Sañonama, Santa Anita and Espíritu.

During the slash-and-burn season, which begins in August, the spread of fire is a nightmare for community members. This practice has always been conducted to prepare the soil, but since 2019 it has exploded. Burning is intended to clean the cultivation areas of small and large soybean, corn, and bean producers. However, uncontrolled fires started by entrepreneurs affect small communities.

In 2019, eighty thousand Bolivians in these communities paid fines for heat spots. Arlena Algarañaz, Germinda’s best friend, remembers the many hours spent at the Forest and Land Inspection and Control Authority (ABT) offices angrily explaining to public servants that the fires had not been caused by community members.

In Sañonama, the thirty-five-degree temperature makes clothes uncomfortable. But Germinda is used to this climate. She is strong and treats these hikes like a stroll. Her athletic agility is due to the fact that she was a soccer, basketball, and volleyball player during her teens.

Although the traditional clothing of the indigenous Chiquitanas is the tipoy —an ankle-length cotton dress— Germinda, like most of her friends, saves this garment for festive activities. She is usually dressed in jeans, a cloth blouse, and tennis shoes, and wears her long hair in a bun.

Classrooms of a school in the community of Santa Anita. Photography: Esther Mamani

She works in the town of San Ignacio —the capital of the municipality—, where the main activity is cattle ranching. It is no longer a tourist resort due to the numerous fires which, year after year, have robbed it of its forest. She has a stall in the main market where she sells udder, blood sausage and everything that can be salvaged from beef.

Germinda was one of the most active participants in the women’s empowerment workshops we used to give with the Ombudsman’s Office and the Comprehensive Family Care Platform,” recalls Arlena.

After noon, several children turn up, fluttering around us like butterflies. We are very close to the only school in Sañomama. Here the women see to lunch while the men participate in a meeting.

The inhabitants of this community try to protect their forests, but they are no match for the fires started by the cattle ranches. This place is surrounded by farms where Bolivian and Brazilian businesspeople are responsible for the uncontrolled burning.

A fight that started at home

It is time to go to another community. The chiefs who sat and discussed all day were the group to which we reported our activities before entering the communities. Leadership by indigenous women has made some progress but there is still a long way to go.

On the way to Santa Anita, I notice Germinda’s well-formed teeth, after seeing her smile. Her sense of humor comes as a relief in the midst of all the hustle and bustle. After two hours on the gravel road and with a lot of dust inside the taxi, we reach our second destination.

Germinda greets the leaders in the new community and takes the opportunity to see the work plans now that the burning has begun.

The leader is a good administrator despite the lack of funds of the Organization of Chiquitana Women. She does wonders with the money, stretching it to cover gasoline expenses so that they can travel between communities. She acquired this ability at her first job when she was still a teenager, at a farm where she was responsible for basic service payments and personnel control.

Because Germinda’s parents took her out of school at fifteen so her older brother could go to college, two years later she was not only working and taking care of their children, but also going to night school to complete high school. Continuing with her education was vital because she was clear about one thing: she did not want to follow in her mother’s footsteps.

“When she was eight years old, my grandparents sold her to a rich family to help around the house and she never went back to school again,” she says, referring to the practice known as patronage, which involves looking for wealthy families to take care of one’s children.

Residents of Santa Anita. Photography: Esther Mamani

Her husband, whom she married when she was about 16, did not approve of her studying and working at the same time. Moreover, he was always jealous of her when she went out and beat and insulted her for years.

But the nightmare ended when he told her to “save money for your coffin.” So, 2015 was a year of change. Not only did she separate from her husband, but she also became a leader.

Now she had left her partner, Germinda saw a clear path to continue her training by attending workshops and occupying positions where she demonstrated her strong, conciliatory, and responsible character.

She is no stranger to criticism. At the entrance to the community, we stop near a church under construction. There, one of the community leaders takes me aside to say that they do not recognize Germinda as an authority and brand her as an NGOer, a derogatory way of saying she works with Non-Governmental Organizations.

“Didn’t she do the work, or did she do it badly?” I ask.

“Why does a woman have to go everywhere? Who has appointed her?” he retorts, without answering my question.

It was certainly not the local chiefs who chose her to represent them in Chile. Germinda’s election had more support from indigenous women.

In addition to fighting fire, Germinda—a mother of three—combats violence against women, which is why she created the League of Community Defenders in 2018. This authority reports on the cases of violence that affect many community members in the municipality.

“Germinda is always willing to help other women and if we hear of a case of violence, we report it,” explains Elena Guasese, an indigenous woman.Most of the reports the League receives are due to abandonment, since fathers disappear for up to four months. In some cases, the men go to work on the haciendas, where they earn eighty to a hundred bolivianos a day from crops or harvesting.

We are now at the home of María Fátima Putaré, a former chief, and while we eat the famous Chiquitana almonds, our guide wipes the smile off our faces. On learning that one of the chiefs was dismissed because he failed to organize the feast in honor of the local patron saint, her face changes and her voice rises.

As a result, the leader calls a meeting and upbraids those who prioritized a social event over all the work of the former chief Rúben Dorado, and summarily dismissed him. It is not yet seven on a Sunday morning and those who are awake respect that decision. “You must obey the statutes (on the management of the authorities),” she admonishes them.

In this community, not all the houses have drinking water and the electric pump is not working as well as it when it was delivered. Droughts affect the basic activities of families, the care of their animals and their production.

Around noon, one of the families invites us in for patasca. This delicacy consists of beef, pork, and boiled wheat in a chili broth. While we eat, the local community members remember how difficult it was to obtain water for making food during the fires due to the ash, which also caused diseases such as sore throats, conjunctivitis, and diarrhea in the case of children.

Efforts by Chiquitana families to protect their forests are not only associated with the richness of their biodiversity, but also with the preservation of their culture, represented mainly by the Chiquitana language.

The fight against fire goes on

Signage on the road to the community of Espiritu in San Ignacio de Velasco. Photography: Esther Mamani

The next day, on the way to the community of Espíritu, Germinda calls a couple of firefighters. Fires have broken out again in Candelaria, San Matías and Roboré. The smell of burning revives the terror felt earlier. Espíritu is one of the largest churches in Chiquitania, where people pray before sunrise that the fire will not reach them.

In addition to the fires, something else worries Germinda, who quickens her pace. Her youngest child has a stomach infection. ”Taking him to the hospital is a waste of time. You have to look after him at home because there are no beds, no specialists and you just take the patient on a wasted journey,” she says.

Although one of her relatives will help with this medical care, the Chiquitana leader seems worried. Tasks start to pile up. “Sometimes I think about retiring from all this. Every year it becomes increasingly difficult to cope with the fire,” she says.

In Espiritu, Germinda had arranged meetings with women to discuss drinking water, education, and health, but now their conversations focus on the heat spots.

After the last meeting, she touches her forehead, fixes her cap, and declares that the visit to the communities is over. She smiles as if to tell me she enjoyed addressing the International Court of Nature, but that here in the forests, no ruling will douse the flames.

This report is part of the Defenders of the Territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformacion.

Leave a Reply