Isabel, the woman who defends the river for which her husband was imprisoned

JODY GARCÍA

(GUATEMALA)

It was June 2015. Spouses Isabel Matzir and Bernardo Caal and their two daughters traveled 131 kilometers from Santa María Cahabón, in the Alta Verapaz department located in northern Guatemala, to the Central Square of the country’s capital.

That day, thousands of people gathered to protest, calling for the resignation of the then presidential dyad Otto Pérez Molina and Roxana Baldetti, who, weeks before, had been linked to major cases of corruption in their government.

The Caal family, indigenous Q’echies,’ arrived in the capital of the country to celebrate the seventh birthday of their youngest daughter and participate in citizen demonstrations.

“We knew that after lunch we were going to go and shout in the square,” recalled Isabel Matzir.

Ese fue uno de los momentos más importantes de la familia Caal, pero especialmente para Isabel, quien tres años después heredaría junto a sus hijas, el trabajo de defensa del Río Cahabón que por años dirigió su esposo, Bernardo Caal.

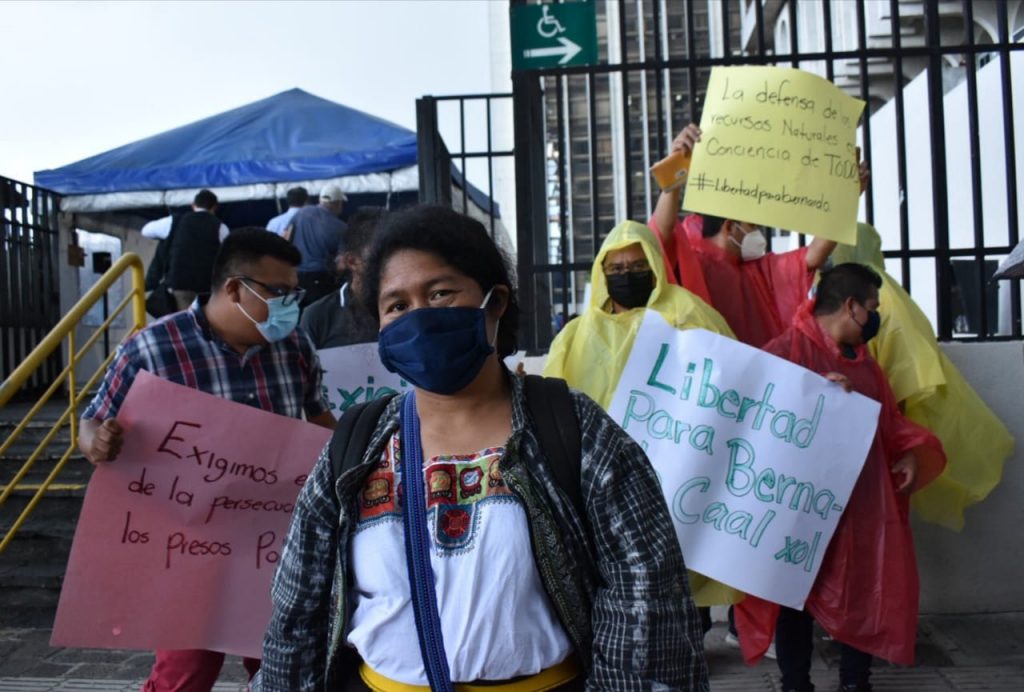

Photo: Ana Cofiño

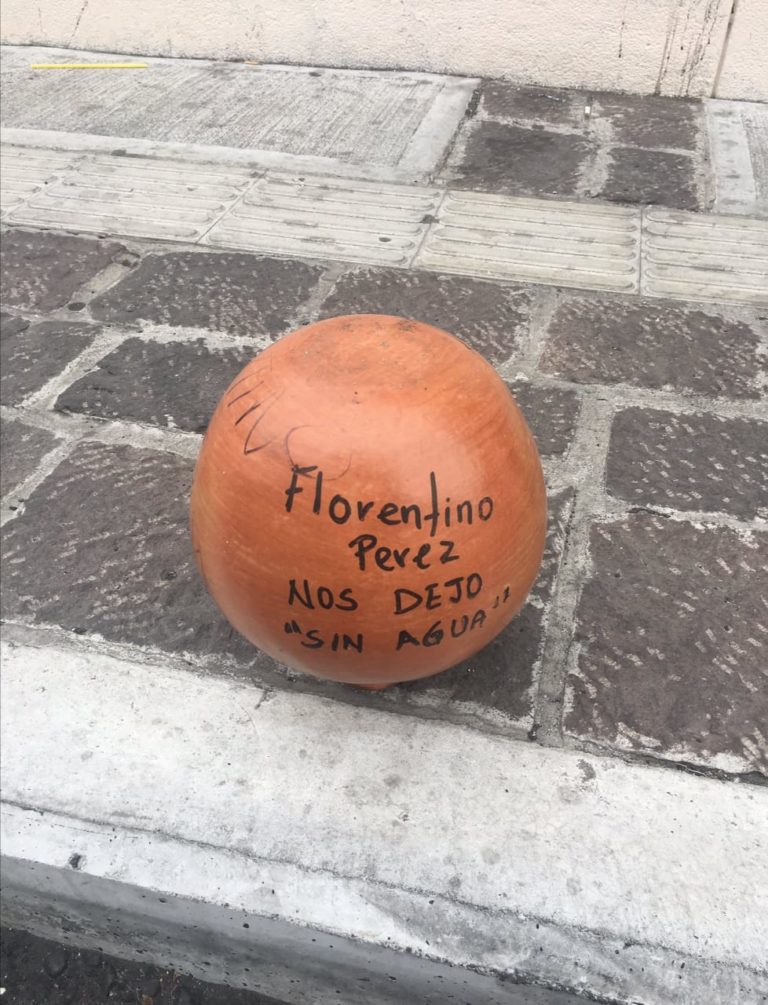

With a length of 196 kilometers, Cahabón River is one of the largest in Guatemala. It runs through the department of Alta Verapaz, where it is the main source of water for the surrounding communities. In 2013, the Guatemalan Ministry of Energy and Mines granted Oxec a license to build a hydroelectric plant that would use the river’s flow. Oxec is part of Grupo Cobra, a consortium chaired by Florentino Pérez, also president of the Spanish soccer team Real Madrid.

Eleven communities directly impacted by the project organized to oppose, defend the water and demand that their right to be consulted ahead of time, in an informed, free manner, as established in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), be respected. Bernardo Caal was one of the most public faces of this movement.

In January 2018, the indigenous leader was captured and indicted on four counts, including the alleged illegal detention of hydroelectric workers. He was reported by Netzone, a company subcontracted by Oxec.

Ten months later, in November 2018, Caal was sentenced to eight years in jail, of which he has served three years and ten months.

Caal’s case was reviewed by the human rights defense organization, Amnesty International, which concluded that the Public Ministry used contradictory testimonials to accuse him, and that it did not analyze the context of the conflict between the community and the hydroelectric plant, or the defense work the community leader was undertaking. Moreover, it declared him a prisoner of conscience and asked the Attorney General of Guatemala, Consuelo Porras, to review the file and start an investigation of the prosecutors involved in the trial.

Over three years later, Caal remains in jail, his lawyers have filed legal actions against the sentence, and now Isabel and her daughters are leading the defense of the Cahabón River while calling for their husband and father be released.

Permission to operate

El 7 de agosto de 2013 el MinOn August 7, 2013, the Guatemalan Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM) published a ministerial agreement in which it granted definitive authorization to Oxec to use the flow of the Cahabón River for a period of 50 years. The permit was signed by Erick Archila, then minister, who is now a fugitive from justice for alleged money laundering while in office.

The Oxec hydroelectric plant has two generating plants that impact eleven communities in Cahabón, Alta Verapaz, and according to MEM, each one has an installed capacity to generate 104,000 kilowatt hours per year. According to the permit file, to which Climate Tracker had access, Oxec invested $63,414,000 in the first part of the project, which was built in 36 months.

The construction schedule, submitted to the Energy Directorate, shows that during construction, the company diverted part of the river for six months, in which it invested four million dollars. But those more than $67 million USD in total are only part of the total cost. According to the documents, the total cost of the project amounted to $143,213,000 dollars. Prior to setting up business, the company purchased over one billion square meters of land.

In a notarial certificate and under oath, the company promised not to affect the permanent exercise of other existing rights, although it did not specify what other rights it was referring to, regarding the use of the riverbed.

Photo: Jody García

Although procedures to obtain the permit began in 2012, the community was never consulted. Nevertheless, MEM granted the company a new permit. On February 12, 2015, the ministry issued an agreement authorizing construction of the Oxec II hydroelectric plant, which would have a 45 MW capacity and be installed in the municipality of Santa María Cahabón, Alta Verapaz.

As a result, on December 11, 2015, Bernardo Caal, and other members of the communities in the Oxec impact zone submitted an injunction to the Supreme Court of Justice, alleging that their right to be consulted on the use of the river had been violated.

Three years later, in January 2017, the Court ruled in favor of the indigenous communities and ordered the State of Guatemala to begin the consultation process with the villages of Secatalkab, Pequixul, La Escopeta, Sacta Sector 8, Seasir, Salac 1, Pulisibic, Las Tres Cruces, Sacta, and Chacalté.

Months later, MEM began to share information on the hydroelectric plants and, according to the case file, on November 24, 2017, representatives of the 11 communities “gave their consent for the construction and operation” of the hydroelectric plant. Afterwards, MEM, the company and the villages signed an Agreement for Peace and Sustainable Development with commitments from the company not to affect the environment.

While this was happening, Bernardo Caal was in prison and Isabel Matzir, his wife, was beginning to assume leadership in the defense of her territory, with a different position from what MEM claims she achieved.

The decision to venture into public life

When Amnesty International reviewed Caal’s case, it concluded he was yet another victim of criminalization, the use of criminal law and the justice system to silence defenders of human rights and natural resources.

The Human Rights Law Firm (BDH), which defends Caal, took the case to the Supreme Court of Justice, where it is calling for the annulment of the sentence and Caal’s release. The hearings to fulfil these requirements have been suspended dozens of times due to legal actions taken by companies subcontracted by Oxec.

For Edgar Pérez, director of BDH and defender of Bernardo Caal, the case is indefensible from a technical point of view.

“When the autonomy and objectivity of the Public Ministry is not enforced and the judge is not impartial, it is extremely difficult to mount a defense. The judicial system is incapable of conducting in-depth investigations and passing impartial sentences, and instead seeks a culprit, even though there was none because no crimes were committed,” he explained in an interview for this organization.

Caal’s file, Pérez said, has been reviewed by academic and legal experts who have found inconsistencies and flaws on the part of the prosecution. According to the lawyer, Caal’s arrest caused fear among the defenders of the Cahabón River, who are now also afraid of being prosecuted.

“The pressure comes from certain sectors seeking to use criminal law to silence and subdue someone who dared to challenge the imposition of a project,” he concluded.

Every time there is a hearing, Isabel Matzir and María Caal, Bernardo’s sister, and other members of their community travel to Guatemala City to protest in front of the Court and denounce the fact that the river has been diverted and the communities have no water and to demand the release of the indigenous leader.

Matzir plays a key role in these demonstrations. Before her husband’s arrest, she shunned interviews and journalists. But with her partner in jail, she decided to speak out.

Fotografía: Jody García

“I tried to avoid the cameras, for the safety of our family. When he was arrested, we agreed with Bernardo that if they sentenced him, there was no other way, there was no other option but to go public, and assume the risks, especially for our girls,” she said in an interview for this report.

In 2018, when Caal was arrested, Matzir began to issue statements on behalf of her family and Santa María Cahabón. She also began to communicate the messages her husband gave her from prison.

“It was not easy to start visiting prisons. It was a difficult stage. But we had to defend our spaces and we needed to explain and tell our side of the story,” explained Matzir.

Although being the spokesperson for a movement was new to her, speaking out for her rights is something she had done since she was young. Matzir grew up opposite a military detachment in Alta Verapaz, during the bloodiest years of the civil war in Guatemala, which was where she learned about injustice, and the massacres, and persecution of indigenous peoples. That encouraged her to join social organizations from an early age.

“I became interested in meeting the people who had been the victims of all these injustices; finding out about these testimonials and their struggles inspired my social commitment,” she said.

Between 2002 and 2003 Matzir participated in its first demonstrations. Twenty years later, she still expresses herself by raising her voice in the street, but she now also uses social networks to reach more people.

It was in these social movements that she met Bernardo Caal. Matzir remembers that even when she was pregnant, she participated in marches for the defense of water and their territory.

Her new leadership has elicited negative reactions, especially gender violence.

“As a woman defender, you suffer more, because the first thing they say, not only within the communities but also at the national level, is that we go to meetings or demonstrations to find a lover, and that we are unruly and gossipy. They accuse us of things that degrade us and in this macho society, it is easy for aggressors to do so,” she declares.

Matzir’s behavior is now more guarded. She is more cautious about who she talks to and who she arranges to meet. In addition to defending her territory, calling for her husband’s release, and raising her two daughters, she must also protect her reputation.

“You can no longer lead a normal life. You cannot relax when you are talking to someone because you worry that they will be taking photos and videos of you that will subsequently be manipulated or divulged to discredit you. The fact that this goes unpunished is more damaging to women and makes us more vulnerable.”

Matzir’s strategies to protect herself from attacks involve self-care, since the country lacks the mechanisms to protect the integrity of women defenders.

“In this case, it is very difficult because I also have to go to the prison and I have no way of documenting the conditions of the visits,” she adds.

Her protection measures also include the use of social networks, especially now that her two teenage daughters have begun to speak out publicly.

“One way or another, they participate in this struggle. It has been particularly important for them to have seen it naturally. They know that where there is injustice, they have to denounce it, that they must not keep silent and must try to cope with the fear that exists,” said the land advocate.

There is always a lurking danger for human rights defenders. Criminalization was one of Matzir’s main concerns, since Guatemala is a lethal place for those who defend the land and the environment. In 2020, the international organization Global Witness ranked the country sixth as regards the killings of environmental activists worldwide.

Although the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, also called the Escazú Agreement, came into force in Latin America on April 22, 2021, in real terms, Guatemala lacks the tools to protect human rights and environmental defenders.

The Escazú Agreement is a regional instrument that seeks to guarantee access to information and justice in environmental matters. It has not been ratified by Guatemala.

The Guatemalan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, through Sara Son, of the Social Communication Directorate of the Ministry, told this organization Agencia Ocote, that the agreement is being analyzed by the President’s Office, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Ministry of the Environment and the Judicial Branch. After their opinions have been received, the agreement will also have to be analyzed by Congress and once the legislative branch has issued its verdict, it will have to be submitted for approval by President Alejandro Giammattei.

The agreement obliges the state to take measures that protect and promote the rights of environmental defenders. If ratified, Matzir could do her job in less hostile conditions.

Photo: Jordy García

Why it is harder to be a female defender

“I am aware that they can make up crimes I have committed, murder and kidnap me. I know that all credibility in the justice system has been lost in this country,” said Isabel Matzir.

Her fears are not groundless. According to the Unit for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders in Guatemala (Udefegua), in 2020, 1,055 attacks against persons, communities and defender organizations were reported in the country. Since July 2020, 551 attacks have been documented. Of this total, 42% have targeted women.

The attacks range from defamation, stalking, harassment, and denunciations to illegal and arbitrary arrests.

Jorge Santos, director of Udefegua, said that according to his data, women are more exposed because their work involves “multi-defense.”

“Women human rights defenders engage in a multiplicity of defenses that range from positioning themselves for their territory and natural resources to defending the rights of women and children. There are also many cases where they are simultaneously demanding justice for their criminalized colleagues,” Santos explained.

This sphere of action has seen an increase in aggressions against these women, which are also gender related.

“Women come up against patriarchal considerations of their public activities. If they go out to demonstrate to demand their rights, they are subjected to severe acts of defamation on social networks due to their gender status. This defamation is intended to confine them to the private sphere,” he explained.

Matzir has experienced this. She says she must be careful who she speaks to and spends time with because people can take pictures of her and then attempt to slander her on social networks.

For Udefegua, it is necessary to create special protection mechanisms for women defenders. A simple example of the need for particular strategies is that when a woman is attacked and must leave her territory, for safety reasons, she must not do so alone. Protection must always be sought for her and the relatives under her protection, such as children, parents, and grandparents.

“In the patriarchal system, when a male advocate has to temporarily leave the area, it is easier for him, he does it alone,” Santos said.

The mechanisms that exist to protect women defenders were created by civil society itself. They highlight the self-care strategies promoted by feminist movements.

As a protection measure for defenders of the territory, Santos remarked that Udefegua firmly believes the Guatemalan state must sign and ratify the Escazú Agreement.

The future

Residents of Santa María Cahabón continue to denounce the fact that the Oxec hydroelectric plant diverted part of the Cahabón River, which has left communities without water. To guarantee their rights to a healthy environment, the two daughters of Isabel Matzir and Bernardo Caal joined the struggle.

Both teenagers have inherited their parents’ fight. On October 11, 2020, Nikte’, the couple’s elder daughter, aged 14, engaged in her first political defense action. On that day, when the International Day of the Girl is commemorated, she took the opportunity to publish a video on Bernardo Caal’s social networks, in which she shared her experience of ser hija de un preso político.

“The State of Guatemala has violated the right I have as a child to live with my father. Since 2017, the State of Guatemala has criminalized and persecuted my father, Bernardo Caal. I demand freedom for the Cahabón River, Oxec River, and my father,” declared Nikte’ in her video.

Photo: Jordy García

Her mother supports her declarations and her first steps as a defender.

“My daughters have had to take on big responsibilities that are not common for most girls their age. They have been trained not to wait to be called; they speak out against injustice. The 2015 demonstration was etched in my mind and in my heart, because we did not ignore my daughter’s birthday, but went out to protest afterwards,” recalled Matzir.

The arrest of a community leader has failed to stop the Cahabón River movement. The baton has been passed to women and adolescents who, while protecting the environment, demand that the State create new mechanisms and adopt existing ones that effectively protect defenders.

This report is part of the Defenders of the Territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformacion.

Leave a Reply