The seedbed that resists afforestation

We thought we were never going to eat black watermelon again, but Claudia Cuebas, from the north of Uruguay, revived it. As an agroecological producer, she recovered a seed that seemed lost, multiplied it, and exchanged it at fairs and meetings with other rural producers. Surrounded by pine and eucalyptus trees that have dried up the lagoon where her children used to bathe until a decade ago, she stands up to the climate crisis caused by the spread of afforestation in this South American country.

As they sit round the table after dinner, Claudia Cuebas looks out at the patio, where dogs run, cats glide around stealthily, pigs wait for their food and cows and horses rest. On the seven-hectare horizon, there are rows of pine and eucalyptus trees. Where there was once a ranch made of mud, wood, and plastic, nowadays a vine has managed to survive, and mandarin trees grow. This agro-ecological farm is a space of resistance designed to combat the advance of a monotonous, voracious green landscape.

Claudia Cuebas’ life took a turn in 2011, after what she called “The Speech of Light” she delivered to the state authorities who inaugurated the electrical connection works in Parada Medina. Her journey had begun five years earlier at the UTE offices, where she demanded the thousand meters of cable required for them to have electricity. That was after Ariel, her husband, threatened to leave the countryside if they could not get electricity.

“You don’t miss what you don’t have,” Claudia tells LatFem. For twenty years, she raised four children, cooked, sewed, and wrote by the light of a kerosene lamp in this rural setting. But faced with the family drama and her husband’s threat, she felt she had to do something. She handed out letters to ministers and spoke with the then-Uruguayan President José “Pepe” Mujica to get electricity and have a refrigerator to cool the milk, rather than leaving the bottles buried in the ground. “Claudia spread her wings,” says agricultural engineer Poppy Brunini, a technician from the National Network of Native and Creole Seeds, who advises her and eight other women in a project to defend biodiversity on the Uruguayan border with Brazil.

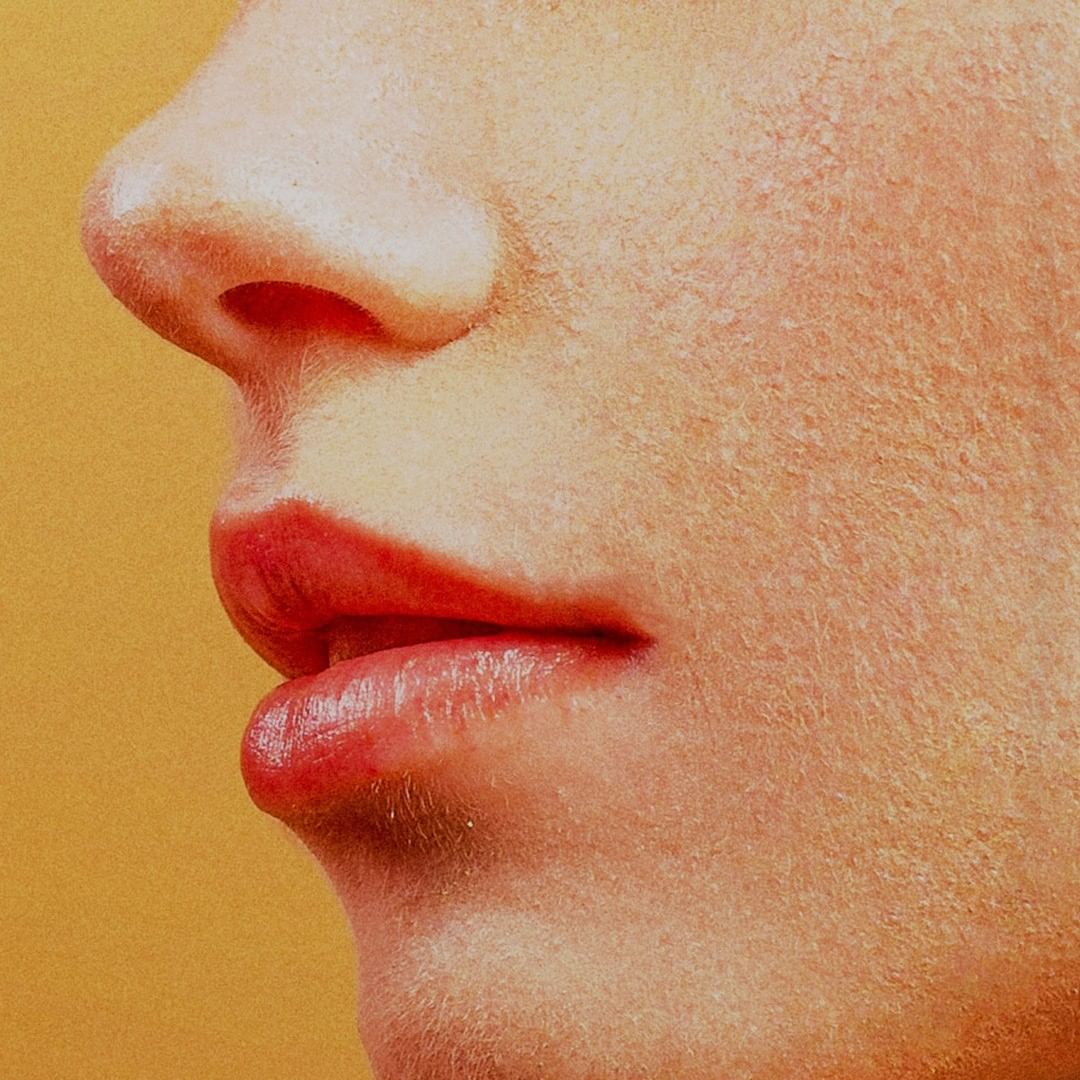

When she left the farm, Claudia met with other family producers and became known for reviving the black watermelon variety in the midst of the 2010 drought. So much so that they invited her to the Seed Network to explain how she had achieved this: she went from being a rural myth to a benchmark. This round-faced woman, with leathery cheekbones and greenish eyes, has her own agroecological method:

“Camilo, a colleague from the Network we formed here in Rivera, had some black and white watermelon seeds he shared with me. That year there was a terrible dry season and the farms collapsed, but I managed to produce black watermelon because I was able to protect it with my compost and one produced seeds. It weighed 25 kilos; it was a real beauty! From then on, I began to recover the seeds and we have already shared them with other neighbors and colleagues. That year I saved the land for the boss—she says, referring to her husband—who wanted to give up everything.”

Claudia remembers who gave her each squash, white bean, creole corn and melon seed. “I collect every seed I see. I am a lifelong seed collector,” she admits. Joining the Network was like going back to her roots, when she lived in the mountains, on the other side of the Río Negro, in Parada Sud (Durazno): “I would walk several kilometers through the fields to get to Pueblo Centenario and go to School No. 39 and on the way I would collect seeds.” If she did not reproduce these creole seeds, she would have to buy “mutant” seeds, as she calls the transgenic ones, at “dollar prices.”

Agroecology makes it possible to retain moisture in the soil all year round, using the “green manure” technique Claudia learned at the More Technologies for Family Production project run by the National Agricultural Research Institute (INIA). This technique involves covering the land with oats months before sowing, to prevent erosion. Federico Rosas, an INIA technician who advised Claudia and four other watermelon producers in 2016, recalls that the Cuebas hectare was the one with the best yield and how difficult it is for other producers to “shift their mindset”. “They harvest in the traditional way one year and the field is destroyed for seven or eight years, so they lease it for afforestation. What’s needed is a cultural change, more awareness between the owner of the land and the person renting it,” says the agronomist.

Claudia used the green manure to perfect her method, which already involved planting “seedlings,” rather than sowing seeds directly. The “Seedlings” are bags with composted soil and watermelon seeds which, once they have germinated, will be planted in the fertile soil. Every season, Claudia assembles between three and four thousand bags by herself.

Photo: Azul Cordo

“No engineer taught me to germinate using seedlings for the Creole seed. I learned it on my own,” she says. It is a solitary, artisanal ritual: she alone turns the soil and prepares the October planting. She produces and harvests on her own because she cannot afford to pay a farm hand. This is also how she combats afforestation on this farm where she has lived for 35 years.

This is almost the same time the ley, which promotes monoculture tree plantations for the wood and pulp industry in “priority forest lands” has been in force. When it was passed in 1987, there were 70,000 forested hectares; nowadays, there are one million. More than 300,000 are fields that should be used for agricultural or livestock activities but using them to plant trees reduces the cost of transporting the latter to processing plants and ports. A new bill seeking limitar la explotación forestal obtained half-approval in late 2020, but President Luis Lacalle Pou said he would veto the law if it were approved by the Senate. Of the one million hectares with monocultures, 80% correspond to eucalyptus and 18% to pines. Rivera, where Claudia lives, is the most forested department in the country.

“Anything that limits this process is good, but I think the proposal for the new project has been poorly framed,” says Marcel Achkar, coordinator of the Laboratory for Sustainable Development and Environmental Management of the Territory at the Science Faculty of the University of the Republic (Udelar). Although the text proposes reducing the amount of forest priority land from four to 1.6 million hectares, this would involve building a fourth pulp mill.

The pulp mills are concentrated in areas close to the forestations. “That is the bane of countries dependent on commodities, it’s part of a macroeconomic strategy of underdevelopment,” continues Achkar. Three hours from Claudia’s farm, in Paso de los Toros (Tacuarembó), the third pulp mill in the country is under construction: UPM2.

It is ten in the morning and the boss orders the piglets born a few days ago to be vaccinated. Claudia puts down her seedlings and goes to fetch the syringes. She walks to the back, where her nephew Diogo is waiting for her with a piglet in his arms and stands in front of the immense eucalyptus trees. “Before we could see everything up to there, to the next house, which is ten kilometers away,” he says, drawing a line on the horizon with his right hand.

Claudia despairs of the advance of afforestation which, in the twenty years she has been in the area, has dried up the natural waters where her children used to bathe and play, or turned them green. Geographer Agustín Urtiaga says in his thesis “Potenciales impactos territoriales de la expansión forestal asociada a UPM2” (Udelar, 2020) that, since 2008, water flows in the north of the country has decreased by 77%. There has also been an “almost total” displacement of fauna, loss of biodiversity and soil erosion, in addition to job insecurity, internal migration of young people for seasonal work in sawmills and pastures, and health effects due to contact with pesticides.

Rivera contains 17% of the million hectares planted with eucalyptus and pine trees in the country and the products of the local forest industry are exported to 35 countries. FYMNSA instalada en 1974, bought up nearly all the fields adjacent to Claudia’s farm. The conglomerate includes afforestation, a sawmill (Dank SA) and biomass power generation (Ponlar SA). There are few neighbors left, and no children nearby. The number of students at rural schools fell from several hundred to no more than thirty.

Photo: Azul Cordo

“In forested basins, water availability decreases by 40% compared to natural grassland basins and, in times of drought, this can reach 80%. Defenders of afforestation say it decreases floods. This is not true: if storms produce more than average rainfall, the ground is unable to absorb it,” says Achkar.

The “umbrella effect” of forested foliage does not allow rainwater to percolate and recharge water tables and aquifers. The amount of chemicals used to prepare the soil, ash, and waste branches, acidify, and degrade the soil. “After several rounds of afforestation, it takes several dozen years for soils to recover. It is undoubtedly more expensive to restore this soil than to buy new soil,” explains the doctor in agronomic sciences.

Photo: Azul Corzo

Before getting up to light the wood stove, Claudia sighs five times. It’s 5:30. With each exhalation, she says, “Ow!”

“I’m going to swallow some pills to start my crazy day.”

At 52, Claudia takes calcium, collagen, two 750 mg paracetamol tablets and is given an injection. At night, she has a massage with ointment for horses.

“If I don’t control the pain, I can’t walk. The twinges evolved into a hernia from here,” she stretches her neck, “to the sciatic nerve.” She twists a little, lifts her hips and strokes her skin with her left hand where it is thickest. “Can you see? I’ve got a lump like an egg here.”

The twenty piglets cannot go without their morning and evening rations for a single day. Claudia loads the wheelbarrow with two buckets and leaves the skins of the vegetables and fruits she has discarded, water with a mixture of sorghum, corn and oats, and organ meats, in the corral. The piglets squeal: only they could possibly find this appealing.

“I go around all day smelling like a pig,” Claudia says later, untangling her long, freshly washed wavy hair. She went to a hairdresser’s once; when she found out her hair was fashionable, she did not go back again.

Claudia prepares the bitter mate tea and takes short steps to reach her own room: the greenhouse. She lifts the thick plastic, opens the mosquito net door, and begins preparing the bags where the watermelons she will plant during the first ten days of October will germinate. Last year she harvested 162,000 kilos of watermelon by herself in this corner of Rivera.

She kneads the soil, greets the earthworms, and checks there are no eggshells or residue from the oranges. Her short nails turn black; the soil works its way into every groove in her hand.

CLAUDIA CUEBAS

In the fields adjacent to the farm where Claudia and her family live, free from afforestation or pasture for livestock, watermelon is intensively produced. Although they use glyphosate, “it is riddled with bugs.” If it rains very hard, the land floods because of soil erosion and the product loses its flavor. “On the other hand, they ask me if I add sugar to mine because of how sweet they are!” she says proudly. To achieve this, she carries a 20-liter backpack on her strained back and applies bostol, a homemade biofertilizer made from fermented fresh cow or horse manure, nettles, molasses, sugar, and fruit peel. She also keeps pests at bay with concoctions made from vinegar, garlic, and a few magical ingredients.

“You make a top-quality product, and they pay you the same as contaminated watermelon. In the first harvest, at the beginning of December, the fruit is worth 20 pesos per kilo; by mid-January, it drops to five pesos. The problem is the commercialization and lack of agro-ecological certification,” says William, Claudia’s second son. The 31-year-old man talks as he gathers logs to make charcoal for this Sunday’s barbecue, in August. It is winter, but the temperature will rise from 9 to 27 degrees throughout the day.

Although a law passed unanimously in 2018 promotes a National Agroecology Plan (NAP) for local production, the incumbent government does not approve of what was agreed on and has postponed its implementation. In the creation of the NAP, la Red de Semillas Nativas y Criollas fue un actor clave para pensar estrategias y desarrollar contenidos.

William watches his mother put together the first watermelon seedlings. The young man remembers the times he worked in pine harvesting and planting.

“The downside is the pollution, and handling poison, but it is the only way to earn a living. In the forest, they apply the poison by hand, they burn their skin while they carry the backpacks, but people don’t protest. You obviously need work, but I’m disappointed they don’t protest to get better working conditions. They make us responsible for recycling and conserving nature, but the big polluters don’t change anything. We are not the problem.”

The forestry industry creates about 18,000 direct jobs in the country, including nurseries, forestry, operations, suppliers, and transportation. The pulp mills did not halt production even after the coronavirus pandemic had been declared.

Photo: Azul Cordo

Forestation exacerbates the effects of climate change in the country. Phenomena such as drought have been recorded to the north, in Rivera, Artigas, Bella Unión, Salto and Young, where the rains began to decline intermittently, beginning in October 1998, during the La Niña phase. “Climate change is awful, you no longer have an exact date, it has changed the cycle of plants,” says Claudia.

La Niña is expected again next summer and may bring more dry seasons. In 2020 la sequía afectó a 1500 productores familiares ganaderos, lecheros, hortofrutícolas y 300 apicultores. Despite this, thanks to the agroecological management of her farm, Claudia had one of her best harvests: “I planted and harvested four hectares of delicious watermelons,” she declares triumphantly. This year, of the 16 million hectares assigned for commercial production and exploitation in Uruguay, 14 millones fueron comprendidas en la declaración de emergencia agropecuaria por déficit hídrico.

Photo: Azul Cordo

As a family producer, Claudia consumes and sells what she produces. Every window, bag of plaster or piece of ceramics was paid for with a watermelon harvest or meat, but she does not belong to the 22.5% of family producers who own their land. Her husband bought the farm, and she produces on the hectare that he lets her use every season. She has already lost land that had been fertilized with oats because Ariel allows the cows to trample over it or the people in the forestry company knock down the barbed wire fence and a stray bull wanders in.

When summer comes and Claudia goes back to work at her stall on Route 5, 1500 meters from her home, the routine will be more complicated: “I have to get up early, do all the usual housework, harvest the watermelon and go to the stall on the motorcycle that has the same aches and pains as me.” After spending the entire day at the stall, she will come back at night and have to do the cooking and cleaning, feed the pigs and the menfolk, and only then have a little rest. The next day she will have to do the same thing all over again, all summer, in the harvest and at her stall.

At ten o’clock at night, after the boss and Lucas have turned in for the night, one listening to the radio, the other scrolling through Instagram, Claudia watches an O Globo soap where they solve problems by yelling at each other or writes a poem to let off steam. She makes a concoction to relieve the pain, pouring a mixture of alcohol, cinnamon, ginger, and nettle into a plastic bottle.

She finally has a bit of peace and quiet.

“The night is my ally.”

This report by Azul Cordo is part of the Defenders of the territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformación.

Leave a Reply