Fernanda Castro Purran, the Mapuche Pewenche champion of free rivers

For the indigenous and environmental organizations of the Bíobío river basin, dams do not constitute clean energy. A fourth hydroelectric plant is being built there, and Fernanda is one of the main leaders opposing it. At 29, she is the director of the Ríos to Rivers Chile organization, a mother and the founder of the Pehuenche Malen Leubü women’s rafting team. She leads meetings and mobilizes young people who are inspired by former environmental defenders.

Fernanda Castro Purran hails from the Callaqui community in Alto Bíobío in southern Chile. This territory belongs to the Pewenche, the “people of the pewen” or monkey puzzle tree, which is sacred to the Mapuche people. It is home to the Bíobío, one of the mightiest rivers in Chile, which has been interrupted by three mega hydroelectric plants: Pangue in 1996, Ralco in 2004 and Angostura in 2014. Today it is being intervened in again, but the slogan of Fernanda and many of the inhabitants who oppose the new projects is “For Free Rivers.”

This young Mapuche woman, together with indigenous communities and environmentalists, contends that the fourth plant, Rucalhue, being built by the Chinese transnational, Three Gorges Corporation, will exacerbate the irreversible impact on biodiversity. The company depicts its project as “clean and renewable” and has already had its Environmental Qualification Resolution approved, but for the defenders of the Bíobío river basin, dams do not constitute clean energy.

“Dams produce large amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas that is more powerful than carbon dioxide. Worldwide, the construction of dams has displaced and affected thousands of indigenous communities, fragmenting their territory, and destroying their traditional life systems. Dams have a negative influence on the quantity and quality of the population’s drinking water supply as well as a devastating effect on local ecosystems and biodiversity throughout the entire basin,” according to the Pehuenche Malen Leubü women’s rafting team, founded by Fernanda.

Another project they describe as a threat to the river is the Water Highway of the Reguemos Chile Corporation, chaired by agro-industrial businessman Juan Sutil. The aim is to build a large, five-section irrigation canal to extract water from the Queuco River—a tributary of the Biobío River—from the Bíobío Region to the Atacama Region, more than a thousand kilometers further north. “We will fight to the end to stop it from being built,” Fernanda has often said of the Water Highway.

Fernanda, together with Paula Riffo Vallejos, spokesperson for the movement against the Rucalhue Power Plant, traveled to Glasgow for the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 26) to talk about the impact of both projects. To date, they have succeeded in ensuring that no further sections to be built have been announced.

“No river has too much water”

Fernanda experienced a turning-point in her life that triggered her commitment to the environment. 2013 saw the death of Nicolasa Quintremán Calpán, a Pewenche activist from the Ralco Lepoy community in the Alto Bíobío district, who was nationally and internationally renowned for her and her sister Bertha’s vehement opposition to the construction of the Endesa Ralco hydroelectric plant. The project, which began to be built in 1997, not only led to the exile and subsequent relocation of the Pewenche families that lived there but also flooded sacred burial grounds.

The young Fernanda was serving an internship in tourism when Nicolasa Quintreman died. During the wake, she felt as though she had been “slapped in the face.” She began to question her life and what was happening in the territory. She started to read more and become both concerned and involved. “The Pewenche territory of Alto Bíobío has been wounded and impacted by hydroelectric constructions,” she says.

Nowadays, Nicolasa is a symbol of the struggle of the Mapuche people against major infrastructure construction projects. This opposition, considered the first Chilean environmental movement, has managed to halt construction of the hydroelectric megaproject on two occasions.

“There is no reason for me to leave. I will leave my land, but not alive,” Nicolasa Quintremán used to say. Paradoxically, it was in Lake Ralco itself, artificially built in this dam, that she lost her life at the age of 74. Her body appeared submerged in the waters on December 24, 2013,” indicó El País .

After years of indigenous opposition and pressure from the state apparatus and Endesa, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights established an agreement between the Chilean state and the Mapuche-Pewenche communities, ensuring that no new hydroelectric projects would be installed on the Bíobío River. This agreement is currently being violated.

“Nicolasa fought against the reservoir and while we were bidding her farewell from this land, I thought that this would not go on happening. They gave everything; it was a fight that lasted many years, in which they resisted. We often simply hear recriminations because in the end, faced with so much pressure, they were forced to negotiate, but they are an example,” reflects Fernanda.

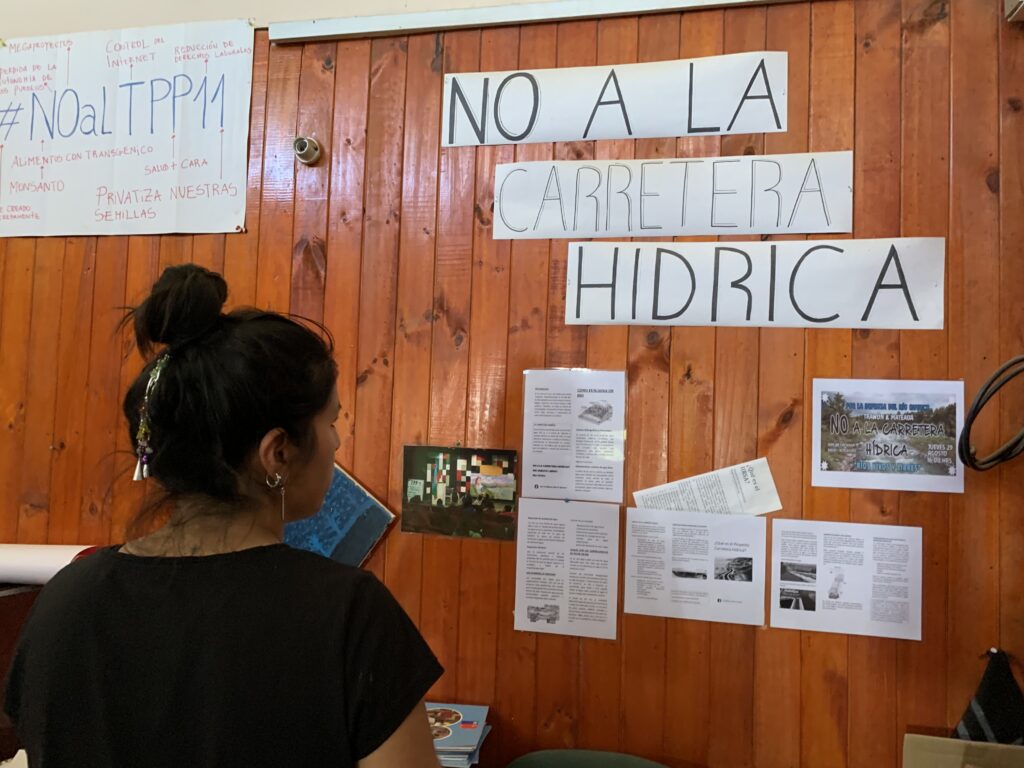

Fernanda Castro Purran at the XX cultural center, which honors Nicolasa Quintreman

Fernanda began to question herself more deeply, since she had studied tourism with a grant from the Pehuén Foundation, a nonprofit established in 1992 by the Central Hidroeléctrica Pangue company, a subsidiary of Enel Generación. “How could I have studied with money from this foundation that did so much harm?” I wondered. I gradually made decisions. Over time, I gathered more information.”

She read the book “Aguas turbias: la Central Hidroeléctrica Ralco en el Alto Bío Bío” de Jorge Moraga, which made her cry on several occasions.

After graduating from higher education, Fernanda worked at an NGO. Shortly afterwards, she taught tourism at Ralco High School, from which she had graduated. She regarded it as a challenge. She was 23, so only slightly older than her students. At the same time, she completed a diploma course in pedagogy in secondary education.

Fernanda worked at the high school for four years. At the same time, she studied pedagogy for teachers thanks to a grant at the University of Concepción. During her last spell as a teacher, she began to be questioned about her participation in marches and demonstrations “against extractivism.” She showed her students the documentary “Turn it off and let’s go,” containing a series of interviews in which those affected provide testimonials of the way their lands were taken from them. Fernanda had to explain her decision as a pedagogue. Eventually, in 2018, the tourism degree course at the high school was eliminated and she was told she would no longer be able to continue working there.

Fernanda Castro Purrán began to devote even more time to the defense of the territory and its waters. At present, at the age of 29, she is the director of the Ríos to Rivers Chile organization, an international movement founded in 2012. It arranges exchanges of river defenders through programs that include indigenous students and community leaders. One of the main struggles of its members has been to stop dams from being considered valid measures to combat climate change.

In March 2021, Fernanda directed the Environmental Leadership Program for Protectors of the Queuco River, designed for young people, tour guides, athletes, and inhabitants of Mapuche communities who participate in emerging organizations dedicated to protecting the territories. This is one of the many activities Fernanda has led, because in addition to communication work, she participates in in-person and virtual meetings and is engaged in continuous training, supported by her territory and networks.

As a member of the movement for the Defense of the Queuco River and the Network for Free Rivers, Fernanda has invited people to mobilize against the Water Highway. The project, promoted by Corporación Reguemos Chile, as indicated on its website, “will allow the capture, storage, and transport of excess water from the rivers of the Bíobío Region, where it is abundant and not used to its fullest capacity in the winter months, to the Atacama Region in the north, where water is scarce and required for different uses, such as agriculture.

However, for the inhabitants who oppose this, “No river has too much water.” We cannot allow our territory to be impacted again by a project as harmful as the Water Highway. We will fight to the end to stop it from being built,” says Fernanda.

Family legacy

When Fernanda was a little girl, she and her classmates witnessed the arrival of large machines, but at the time, they did not understand the impact they would have on the area. What she was always aware of was the need to respect Ñuke Mapu (mother earth). She mainly inherited knowledge from her grandmother Rosa Milla, who died 10 years ago. Rosa taught her about Mapuche spirituality and the fact that “every element of the earth is alive.”

“In her daily work, Fernanda reflects what our grandmother taught us when we were small, about taking care of nature and the river. Sometimes we would go to spend the night with her. Fernanda is an example to follow, she is a good leader. The whole family is very proud of what she does,” says Paulina Purran (31), Fernanda’s first cousin. They grew up together and currently share various activities such as playing palín, a traditional Mapuche game.

The people around Fernanda describe her as an extremely organized, structured woman, which enables her to participate and lead all the activities she engages in daily. She has a strong character, and is a good mother, and above all, a loyal person who likes to dream.

“Although sometimes she gets disheartened, she has a strong, resilient character that has enabled her to be the leader she is. She is also respected for her work in the territories,” says Paulina Purran, who also mentions the Quintreman sisters as outstanding women and Mapuche. The cousins think it is essential to transmit this knowledge to their daughters.

Fernanda’s life, like that of many indigenous peoples, was marked by poverty. From the age of 12 to 16, she used to work as a seasonal fruit picker in the summer in various places with her cousins, mother, and aunts. When she was in the last year of high school, she became a mother. She remembers this process as being difficult, but one she was able to cope with because she had a lot of family support.

Her aunt, María Purran Milla, explains that Fernanda has been enthusiastic about her studies, independent and sociable since she was a child. “She began to mobilize a lot of people. She has fought to defend the environment. I think she inherited that strength from my father, because he was a great fighter who always defended our ancestors, his community. Fernanda has been to other countries to tell them what is happening here. I am proud of my niece, because we have to take care of the rivers,” she says.

María, the oldest of her siblings, was 14 when in 1973, her father José Guillermo Purrán Treca was arrested and disappeared, a victim of the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. He was a leader and recognized at a territorial level. He toured various communities on horseback, recovering land for other families.

“My father was killed for speaking out, for being a Mapuche who defended the environment. To this day, we are still seeking justice, like many people in the territory. That hurts; it marks you for life. It’s a wretched memory we have. My father was not a terrorist; he died fighting,” explains María.

Another of Fernanda’s aunts, Francisca del Carmen Purran (62), who considers Fernanda her second daughter, describes her as a hard-working, intelligent, brave, and active woman. “I am always asking Chaw Ngünechen to take care of her and protect her. I celebrate the young people who are protecting the territory of the elders.”

Fernanda’s aunt has not been to look at the Bíobío River for over 20 years, even though it is only a few yards away. It makes her sad. “It has made me miserable since Pangue was built. It is heartbreaking to remember what it was like before and see what it is like now. There were fast-flowing rivers, and now it is like a small estuary. One day I went to the Queuco viewpoint and thought, what would happen if the water highway was built? It would dry up,” says Francisca Purran.

Inspiration for others

“Feña” as Fernanda’s friends and family call her, is also a rafting and mountain guide. She usually cycles around the area, often accompanied by her 12-year-old daughter. They regard each other as partners. Fernanda speaks softly to her daughter, but she is also strict.

Her friend, Néstor Queupil Naupa from the Cauñicu community, thinks that Fernanda is a leader in the territory, mainly because there are people who respect and follow her. She also has a great ability to create networks. “She attracts a lot of people, because she is very unassuming, and she has a level of maturity and perseverance that those responsibilities require. She is always willing to talk about any issue, and eager to hear the opinions of all those who are involved in a conflict. She is an example for many people in the territory.”

Néstor, who is also a teacher of Chedungun (a Mapuche language), reflects on the fact that many of the socio-environmental leaders who have existed in the territory have been women “who have perhaps not been publicly recognized. There is a lot of female leadership in these struggles. They all sacrifice a part of their lives.” In this respect, Néstor believes that the role of young people is crucial to the protection of the territory, so that the “stories of deception by companies” are not repeated.

Fernanda at the XX headquarters where self-training work has been carried out.

Tannya Ormeño Treca (21), from the community of Callaqui del Alto Bíobío, was one of Fernanda’s tourism students at Ralco High School. She saw Fernanda as a teacher who inspired them. “She took us out to the mountains, and taught us to take care of the river, and to ensure that tourism had the least possible impact. She was very patient with us.”

The two women traveled to the Argentinian Patagonia together as part of the Ríos to Rivers exchange, where they rowed. There she saw Fernanda leading in the field. “She is brave and inspires us to continue. We now see the water highway as the greatest threat, in addition to the damage caused by those that have already been built. That is why she has spoken up, to show us that the river must always flow freely. She has gone to various territories to drum up support.” “I am proud of her as a woman and a Mapuche Pewenche. She always says, “I won’t rest until the Bíobío River is free,” says Tannya.

Felipe Purran Pichanao (44) from Callaqui, a relative and a neighbor of Fernanda’s, notes that people in the area say that Fernanda is unpretentious. Above all, in the face of “the threat of the Water Highway, she has studied together with her organization, educating people about the damage it will cause if it is built, so the community has been keeping an eye out. Everything she learns, she shares.”

“Today there is such destructive development that what we do is defend Itro fill mogen (biodiversity). Water is life, it has to be clean. Feña has understood that well and therefore defends it. Like many of her generation, she lost her language because of the discrimination our parents experienced, but she took in the kimün (knowledge) her grandmother and family passed on to her,” he concludes by saying.

This report was originally published in Interferencia on March 26, 2022, as part of the “Women Defensing their territory” project of Climate Tracker and FES Transformación

Leave a Reply