The Women’s Advocate against Fracking

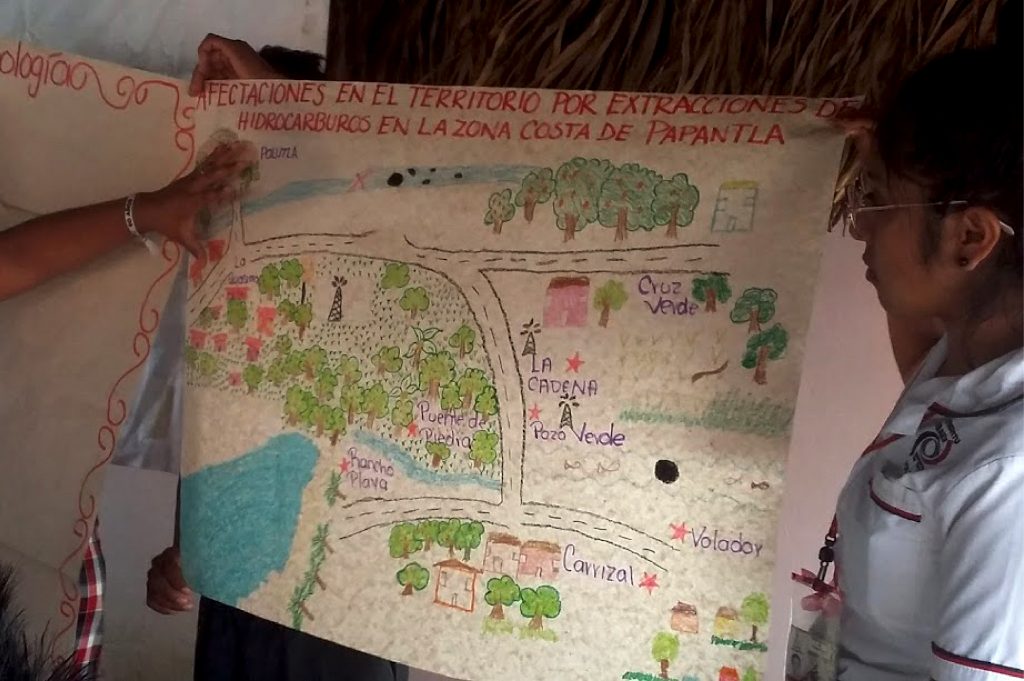

In the Totonacapan region in Mexico, a woman has spoken out on behalf of her companions to stop an extractive activity the government insists on denying.

Photo courtesy of Alejandra Jiménez

Corn, orange, and vanilla crops are interwoven with the plains where cattle graze and forest areas in Totonacapan. This region includes parts of the states of Puebla and Veracruz in the easternmost point of Mexico, although since pre-Hispanic times the actual borders of its forests have been the sea, the mountains, and rivers.

At first glance, the fertility of Totonacapan seems indestructible. However, women like Alejandra Jiménez, 42, have had to defend it from decades of dispossession, exploitation, and environmental and social impact by the oil industry. Now fracking joins the list of threats.

“What first motivated me was seeing the amount of oil wells around me, among the trees, in the middle of the communities, near my children’s school,” says Alejandra in an interview about her activism, “but then the behavior of companies that profit from the environment, injustice and imbalance in the region also inspired me to protect other people.”

Today she is fighting against a new danger that looms over the territory, particularly its defenders. Fracking or hydraulic fracturing is an unconventional technique for extracting fuel—gas and oil—that can pose greater risks for women in the form of cancer, premature births, economic dependence, and prostitution.

In Mexico, fracking was relatively unknown before Energy Reform, which came into force under 21 de diciembre de 2013 during the government of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018). Since then, hydraulic fracturing has been introduced into the country legally, but the CartoCrítica organization has documented its presence at least desde 1996.

It is also estimated that one out of every four oil wells in Mexico undergoes hydraulic fracturing at some point in its production cycle. And although its specific effects on Mexican women have yet to be studied, Alejandra Jiménez notes ha denunciado that the experience of other nations clearly shows differentiated gender-related impacts.

“I would say that all extractive industries affect men and women differently, and fracking is no exception. In the territory, I realized that because women stay at home and undertake care activities, they have to deal with the problems caused by access to water, for example,” notes Alejandra.

Thanks to the work of this advocate, as well as civil and collective organizations, fracking in Mexico has not spread as much as it has in other countries. However, its expansion is a latent threat, despite the fact that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) declared that fracking would be prohibited during his administration.

“We are going to extract oil, but without fracking, without affecting the environment and without affecting aquifers,” he declared in octubre de 2018 when he was president-elect. A couple of months later, these words became the 75th of the 100 commitments AMLO made when he came to power. By December 2019, the promise was listed as cumplida.

However, the Mexican Alliance against Fracking, created in 2013, to which Alejandra Jiménez belongs, estimates that in 2019, 6.7 billion pesos were assigned to this practice for projects inherited from the previous administration. In 2020, the budget for fracking in Mexico exceeded 10 billion pesos and so far this year, it already amounts to over 4 mil millones de pesos.

“Of course, there is fracking in Totonacapan. They are using all the legal scaffolding left by the Peña Nieto administration, except that the current government repeatedly and blatantly denies it, which is very unfortunate, sad and makes me incredibly angry,” says Alejandra.

Country woman stuck in the city

Alejandra Jiménez describes herself as more of an advocate of life than the territory or the environment. Laughing, she also defines herself as an “country woman stuck in the city,” someone who was born and raised in the city yet has always had an affinity for the countryside.

Her sister Mónica Jiménez, 10 years her senior, notes that Alejandra has had a strong character since she was little. “I remember the first day she went to elementary school. Seeing her with her uniform and backpack in her hand was like seeing a ‘little adult,’ perhaps because of her forthright remarks, thoughts, and the way she spoke, which was more mature than you would expect from a girl her age.”

Before going to university, where she studied anthropology and political science, Alejandra began doing community work in the Sierra Norte de Veracruz, where she eventually spent several years in the community of Huayacocotla. “From a very early age, she wanted to help people and do something altruistic for others,” adds Mónica.

In Huayacocotla, Alejandra taught undergraduate classes and became involved in human rights issues and feminism. Her sister adds that, “I think she got this from my dad, respect for nature and love for others. But the awareness of care comes from my mother: recycling, reusing and conserving water. My mother did not instill this in us so much because of her ecological commitment, but for the sake of the family economy.”

In 2010, Alejandra’s life took a turn that would lead her to become an environmental and territorial advocate. “The year she, her partner and her children arrived here, in Totonacapan, the older one was just learning to walk and the younger one was a babe-in-arms,” says Fermina Pérez Atzin, a farm worker, businessperson and activist leader from the El Remolino community in Veracruz.

Alejandra Jiménez, a powerful voice that has denounced the differentiated effects of fracking on women.

Alejandra and her family settled in El Chote, part of the municipality of Papantla, where the media have reported the presence of some 3,220 pozos petroleross. “I arrived without that many professional expectations, more or less as a housewife,” she admits. However, shortly afterwards, the inhabitants of different communities began to ask for her help with negotiation and conflict mediation.

“That had a huge impact on me. I came from the mountains, from a community as small as Huayacocotla to a territory that was not at all the way I remembered it,” Alejandra admits.

As a girl and subsequently a university student, Alejandra had sometimes visited the Totonacapan region, specifically Papantla, which was a “beautiful” and quiet place in her mind’s eye. That image changed when she became aware of the existence of a phenomenon she had not even imagined.

People told Alejandra that, in the past, Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), the parastate company founded in 1938 and responsible for the hydrocarbon production chain in Mexico, used to compensate communities for the environmental and social damage caused by extractive activity.

“But suddenly PEMEX changed the way it operated. It no longer informed villagers about its actions; it stopped responding to residents’ complaints about the detonations, and it no longer compensated communities for leaks or spills,” explains Alejandra.

According to Nancy Julyeth Martínez, a friend of Alejandra’s from the village of Oriente Medio Día, practically the whole of Totonacapan has been explored, not only by PEMEX, but also by foreign companies.

This has ended up overwhelming communities. “We no longer want pollution to be part of everyday life in the region, oil spills to kill all the life in the streams, our lands to be expropriated, or children to be unable to fall sleep for fear that the oil facilities will explode,” says Nancy.

Alejandra Jiménez heard this cry and, despite not having been born or raised there, she joined the Totonacapan defense until she played an essential role. By then, this was already her territory as well.

Silent enemy

Alejandra had not been in Papantla long before she was invited to participate in a project to recover the milpa. According to the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity, milpa “is a traditional agricultural system comprising polyculture. Its main crop is corn, accompanied by various species of beans, squash, chili peppers, tomatoes, and many others depending on the region.”

Alejandra noted how much knowledge about the milpa in Totonacapan had been lost and how it was replaced by monocropping and widespread agrochemical use. But what surprised her the most was that the farm workers asked her to buy “tons and tons of land.”

“But why do we need to buy land, if the land is here?” she asked them.

“This land is useless,” the farm workers replied. “This land is polluted.”

“They were referring to the spills,” concludes Alejandra.

According to the Oil Spill Prevention and Response organization, oil spilled on the ground prevents it from absorbing water and suffocates plant life. But the problem does not end there, as hydrocarbons can seep into groundwater or be washed into rivers and streams.

For Dr. Victoria Chenaut, a scientist at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS), “From the outset, oil exploitation in the area has undoubtedly caused environmental pollution due to hydrocarbon spills and gas flaring, among other circumstances, affecting crops and residents’ health.”

In the municipality of Papantla alone, this has happened since the 1950s, when PEMEX began to work there intensively. It was subsequently joined by foreign companies, especially as of 2007, when a decline in oil production in the region paved the way for private companies.

In one of her academic publications, Victoria Chenaut relata who visited a plot of ejido land “where an oil spill of thousands of liters occurred for about a month, until PEMEX personnel took all the land that was considered unusable, promising ejido owners they would give them good quality land in return, which they have yet to receive.”

Witnessing this situation led Alejandra to link up with other activists to strengthen the defense of the territory in Totonacapan. However, the onslaught from oil companies was far from being the only threat.

Fracking from a female perspective

“We think that in all territorial defense struggles there are always women whose work is made invisible,” says Nancy Julyeth Martínez, who is also part of CORASON.

For her part, Fermina Pérez Atzin declares that “in our communities, it is quite difficult for us as women to be recognized, valued, respected, when in fact we are the ones who look after the home, children and family maintenance. Women are the ones who clean the streams and look after the wells.”

When Alejandra was asked how she realized that fracking affected her female colleagues differently, she replied: “They have a more critical position. They tend not to collude with oil companies because they don’t even give them jobs. The hydrocarbon industry is predominantly male and forces women to stay at home fulfilling gender roles and stereotypes.”

A study conducted in the United States by National Bureau of Economic Research showed that fracking provides approximately 43 jobs for every 1,000 men, as opposed to only six jobs for every 1,000 women.

Another investigación, prepared by Clemson University in South Carolina, United States, found that most of these jobs do not require specialization, so fracking is linked to higher school dropouts and offers almost no opportunities for highly-skilled women.

Moreover, this gender-related labor inequality tends to trigger male migratory processes to such an extent that in the fracking sites there are even some 10 hombres por cada mujers. And in the long run, these population dynamics can trigger an increase in prostitution among women, a phenomenon widely documented by científicos sociales and periodistas.

In this regard, Alejandra Jiménez says that “El Chote is a cruise ship. There is a road that goes to Poza Rica and another to Papantla, and right there, there are lots of restaurants and bars where the men who work for oil companies are concentrated, and it is awful to see that they ask girls for sexual favors in exchange for 50 or 100 pesos to top up their prepaid cell phones.”

This is a constant in Totonacapan. “While men go off to work in companies as laborers, women have no other option for paid employment than serving as waitresses, in the best cases, or engaging in sex work in the worst,” adds Alejandra.

Gas pipeline in the Totonacapan. Photo courtesy of Alejandra Jiménez.

Another differentiated impact of fracking on women, which often goes unnoticed, concerns mental health. “Women are the ones who spend the most time in the communities,” says Alejandra. “They have to deal with the deafening noise of PEMEX gas burners, for example, live with the continuous fear of having to flee and lose their land or even die in a disaster caused by oil companies.”

Nowadays there is evidence of what Alejandra has mentioned. This is the case in the work of Stephani Malin, a social scientist at Colorado State University. Her research has shown that “living near fracking sites can cause chronic stress and depression,” a consequence that occurs especially in pregnant women, according to a estudio conducted by Columbia University.

Alejandra has also seen how various risks to physical health emerge in these circumstances. “I have found a lot of women who lived near the wells and developed cancer, as well as young women who had premature births; but it is very difficult to link these problems to fracking, since in-depth research and the participation of several actors are needed.”

According to Alejandra, neither academia nor the Mexican health authorities have expressed interest in analyzing the relationship between the hydrocarbon industry and the incidence of certain diseases in regions such as Totonacapan, which has been done in the United States. Experimentos en ratones published in 2018, for example, indicate that contamination by fracking could increase the risk of breast cancer in women, since abnormal development of breast tissue has been observed, even at low concentrations.

And according to a 2016 publication in Nature journal, fracking can release up to 1,021 sustancias into the environment. Of these, 103 have been reported to cause reproductive harm, 95 are toxic during embryonic development, and 41 pose a risk for both.

Consequently, studies have identified that proximity to fracking sites may represent a risk of preterm birth due to air pollution for pregnant 50% más probabilidades women. This type of birth is the leading cause of muerte infantil worldwide.

At the same time, an analysis of over 1 millón de nacimientos before and after fracking was established in Pennsylvania, United States, found that when mothers live within three kilometers of hydraulic fracture sites, babies are more likely to present indicators of poor health, such as low birth weight.

Water contamination by hydrocarbons in the Totonacapan. Photo courtesy of Alejandra Jiménez.

Ajejandra Jiménez declares that, even when a certain woman’s own health is not directly affected, fracking always ends up impacting her quality of life. Because they are the ones who take care of those who get sick from fracking,” she explains.

More than a decade of investigaciones, especially in the United States, shows that fracking impairs people’s health regardless of gender or age. Respiratory problems, migraines, fatigue, skin conditions, nausea, sinusitis, and other ailments are associated with this practice.

It therefore comes as no surprise that in Totonacapan women have shared testimonials with Alejandra such as, “My children started to get rashes on their skin and I had to spend more time washing clothes” or “the children and the men got sick, so we had to take care of them, we had to go further afield to fetch water because the water here was not good, and it took us longer to cook, wash and clean the house, and that prevented us from attending to other matters.”

Alejandra has been the face of these stories in forums such as Tribunal Permanente de los Pueblos, an international benchmark for human rights defense. Likewise, she has appeared before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and collaborated with the group that promoted the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the Escazú Agreement.

Before her ratificación en México, Alejandra was one of those who was most vocal about the fact that this document was a necessity for women, since “violence against women who usually lead the movements to defend the land through public participation is very similar to the violence exerted towards the environment.” In Mexico, the Escazú Agreement came into force on April 22, 2021.

Alejandra Jiménez’s message in this type of forums has been overwhelming: We defend the territory and everything that lives there: the plants, animals, food systems and what gives people life and a place.

Future

“It is impossible not to feel anything when you know your ancestors gave their lives to secure a plot for you, and then outsiders come and break everything up to get oil; it really gets to you,” says Fermina Pérez Atzin, “but Alejandra has helped us interpret what we are experiencing, and act and speak; she has even accompanied us in the riskiest situations, and thanks to her, our struggle has positioned itself in the public space.”

From the Mexican Alliance against Fracking, Claudia Campero agrees with Fermina, adding that “in Mexico, research on fracking is so scarce and insufficient that the work of people like Alejandra is essential to produce information, which is later cited by environmental organizations or even academia.”

Alejandra receives these types of comments modestly and replies that, “To begin with, I cannot dissociate what I do from a group of people, because defense is a collective task.”

Work with Totonacapan communities

However, her leadership is unquestionable, which is how Nancy Julyeth Martínez describes it: “Alejandra is a counselor, warrior and friend. It doesn’t take long to realize that this woman is essential, that she gives herself completely to her work, and that her work lies behind many of our achievements.”

But there are still some issues pending in the defense of Totonacapan against fracking. One of them is to enact a law that prohibits it, not only in that territory but throughout the country. In this regard, at least ocho iniciativas have been submitted that have not progressed in Congress.

For Alejandra Jiménez, the most important task is to reverse the culture of oil, for the inhabitants of the territories no longer to identify with its extraction and for there to be an awareness of the damage caused by this industry.

She concludes by saying, “I believe that we should all be involved in defending the territory; we should not just think about carbon emissions or river and aquifer pollution, but rather that all these problems involve lives.”

She concludes by saying:

“I believe that we should all be involved in defending the territory; we should not just think about carbon emissions or river and aquifer pollution, but rather that all these problems involve lives.”

This report is part of the Defenders of the Territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformacion.

Leave a Reply