Ná Lupita, woman of the clouds in front of the wind

anaiz zamora y greta rico

(méxico)

Guadalupe Ramírez is a woman who comes from the clouds. The strength with which she defends her territory is comparable to that of the wind from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Oaxacan region in the south of Mexico she inhabits and defends. In addition to guarding the land, she protects the air that is capable of overturning trucks carrying 30 tons of merchandise and attracts transnational companies, which, under the guise of creating sustainable energy, violate human rights that the Mexican state only seems to protect on paper.

Originally from one of the villages in the region, Unión Hidalgo, a decade ago (at the age of 60), Guadalupe began teaching herself everything she could about wind energy, international law, agrarian law, and the obligations of the state towards indigenous communities. She decided she would have to be informed to be able to compete against the wind energy companies.

Like the neighboring villages, Unión Hidalgo is a community of indigenous Zapotecs who call themselves Binni’zaa (people who come from the clouds) and use the term Ná to refer to older women. Not only because of her age, but also because of her active role in various community processes, Guadalupe is known as Ná Lupita and many of her colleagues describe her as a brave woman who inspires others to continue fighting.

So far, she has scored one major victory: preventing Desarrollos Eólicos Mexicanos (DEMEX) from putting up wind turbines on the community’s land. In addition, in 2021, together with her community, Ná Lupita took on Électricité de France (EDF), which is attempting to set up the Gunna Sicarú wind farm. She is conducting a two-pronged defense: a lawsuit with a French Court and an injunction ordering the Energy Ministry to conduct a proper indigenous consultation.

She has also challenged the Mexican state, which ratifies international agreements yet does not fulfill them. The installation of wind farms in the region violates the Convenio 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), guaranteeing the right of indigenous peoples to prior, free and informed consultation. For International Law specialists such as Alejandra Ancheita, the recently ratified Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (The Escazú Agreement), which among other measures, seeks to protect environmentalists so that they can act without threats or insecurity, runs the risk of becoming a dead letter.

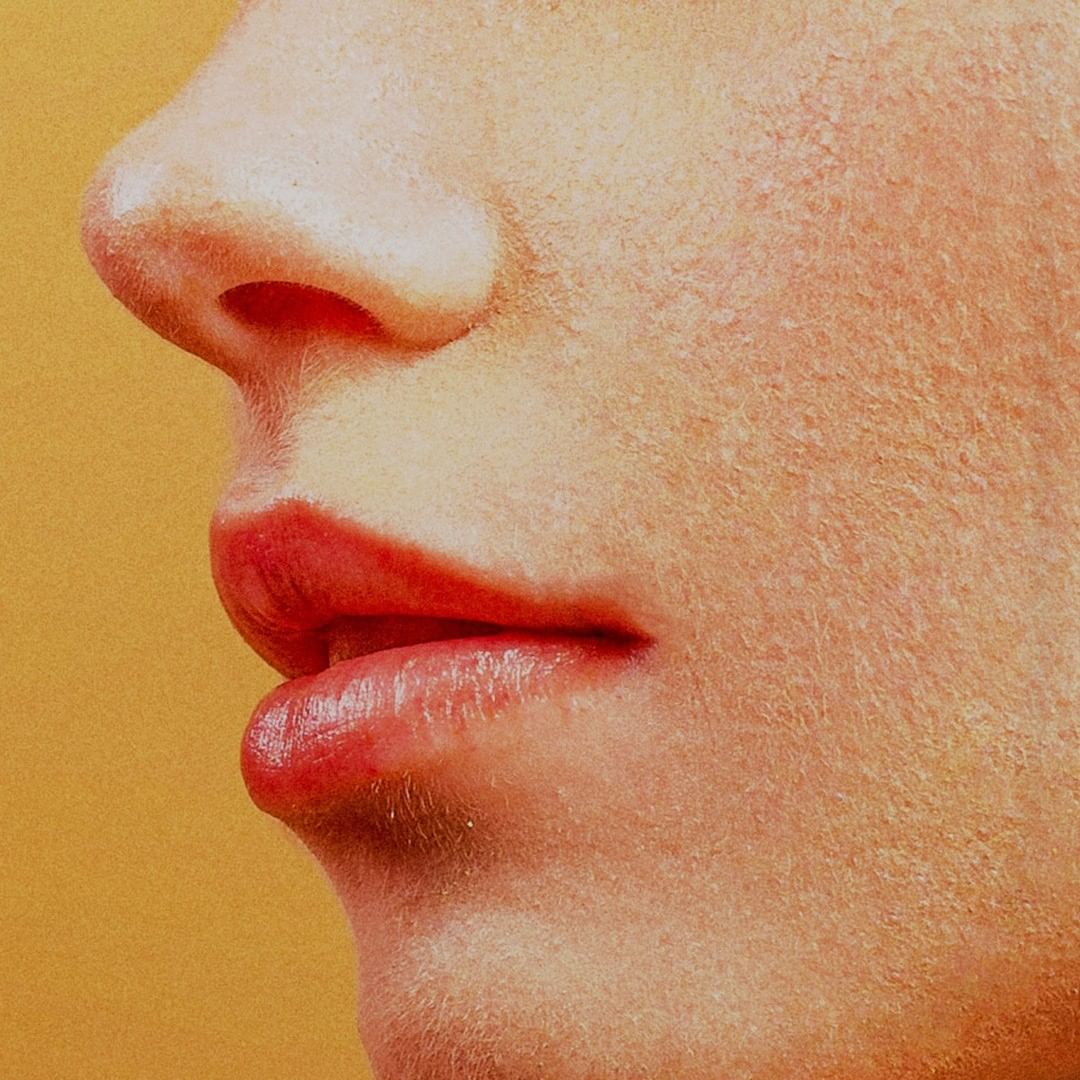

Guadalupe Ramírez, 70, has been defending her territory from wind companies for a decade. Photography: Greta Rico

In the late 1990s, “some very odd weathervanes” began to crop up in the landscape Ná Lupita saw when she left her community. White turbine towers multiplied rapidly in the region. In 1994, the parque piloto conocido como La Venta was set up in Juchitán, a town just 20 minutes from Unión Hidalgo.

It was not until 2011 that Ná Lupita and her husband, Juan Regalado, found out that they were wind turbines. One day, DEMEX, a subsidiary of the Spanish company, Renovalia Energy (recently acquired by the American Investment Fund Cerberus), and a result of the “commitment” of the Bimbo baking company “to work on a sustainable path for a better world, by investing in technology and innovation to reduce their environmental footprint,” knocked on their door, offering them a lease. Ná Lupita and her husband were promised 15,000 pesos a year in exchange for allowing the company to set up wind turbines on their land.

The promises included the fact that they would be able to continue sowing, since the land would not lose its productive capacity and cattle could continue grazing. The couple decided to sign because “the lies they told us did not sound bad at first and they told us it would also benefit the community. At the time we did not realize that they only told us the good things about the project,” explained Ná Lupita in an interview for this report.

It did not take long for Ná Lupita “to realize they had been duped.” She began to see how heavy machinery destroyed everything in its path. “They did not fell the trees, they destroyed them. We could not even use them as firewood,” recalls Rosalba, one of Lupita’s fellow activists, who believes they did this to “destroy the evidence that we have a lot of diversity here in the region.” The presence of flora and fauna in the area where the park was built was confirmed in the Estudio de Impacto Ambiental of the project.

In addition to the sadness they felt at seeing how “in a little while, they turned the trees we had looked after for so many years into dust,” another discovery that led Lupita and her husband to ask for the contract to be canceled was when they went to Financiera Rural to renew the loan that enabled them to buy sorghum seed for planting and found that the company had already mortgaged their land, as if it were the owner, to finance construction of the Piedra Larga wind farm, also located in Unión Hidalgo.

Repealing those contracts was no easy task. After failing to obtain a response from the company, they tried to talk to the governor of Oaxaca. All the affected owners organized to rent a truck and make the six-hour journey separating Unión Hidalgo from the center of the state together. Although they went twice, the governor never received them. “We realized we needed to find a lawyer to help us. It was not just us; another 20 owners were also dissatisfied and so the Resistance Committee was born.”

Juan Antonio López, coordinator of transitional justice in ProDESC, is one of the lawyers who accompany the community. He explains that in 1954, Unión Hidalgo declared itself an agrarian community, as a result of which the lands are communal rather than private property. This means that leasing contracts must be conducted in accordance with agrarian rather than civil law. This has not been done in any of the 28 wind farms now located in the Oaxacan Isthmus, since it would require the entire community to agree with the construction. “That is not in the interests of any company, which is why they decided to hire public notaries to help them,” explains the lawyer.

Ná Lupita learned to defend the land from an early age, when her father had to take on “a lawyer who wanted to take away everything he owned.” Her father won and she learned “that it is possible to win if you don’t give up the fight even when the going gets tough.” Another thing she inherited from her father is her strong character, which has enabled her to form part of the resistance in a community where political participation is usually the province of men.

Ná Lupita’s self-education began when DEMEX arrived in Unión Hidalgo. “To think we did not even know there are Conventions that protect us as indigenous peoples.” She read all the information ProDESC sent her and asked, “a lot of questions to improve my understanding.” During the construction of the Piedra Larga I and II wind farms, the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (ILO Convention 169), in force in Mexico since 1990, was completely ignored by the Mexican government, as no consultation was made.

In 2013, Ná Lupita engaged in her first legal battle, when the disgruntled landowners filed a complaint with the Unitary Agrarian Court of Tuxtepec (Oaxaca) requesting the nullity of the contracts that had been signed with DEMEX, arguing that they had no value because they had not been signed within agrarian law. Although the magistrate admitted that there is a communal regime in Unión Hidalgo in 2016, he did not rule in favor of the community, arguing that the company “had not been notified that this regime existed,” explained the lawyer. ProDESC protected itself against the resolution, but the case has yet to be resolved.

Both Mrs. Guadalupe Ramírez, ‘Na Lupita’, and other people in the community managed to prevent the wind turbines from being installed on their land. For this reason, both in the Demex wind farm and in others on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, empty spaces are observed along the wind farm. Photography: Greta Rico

Ná Lupita has already scored a victory. Just before the Agrarian Court issued that first ruling, in 2015, DEMEX rescinded the contracts of seven owners, including hers.

The company was afraid of being given a sentence that would be disadvantageous for it, which is why they rescinded the contract. “They did not build anything on those lands, which is already a great triumph, and it was possible thanks to the fact that she was dissatisfied and told her colleagues,” explained Juan Antonio

At the moment, the family ranch is surrounded by wind turbines, but has not been invaded. Instead of metal towers, Ná Lupita has fields of sorghum, corn and beans and continues to watch the growth of the fruit trees, which the chickens help fertilize, while her animals have plenty of room to graze.

The gusts of wind on the Isthmus have the strength of category two and three hurricanes, meaning that the area has the second largest wind energy potential in the world. This is well known by companies which, in addition to not sharing their income with the communities, do not share the energy they generate either. The Mexican government is also aware of this since el sexenio del presidente Felipe Calderón no ha cesado de otorgar licitaciones. As a result, the soundscape previously dominated by birds now comprises the ceaseless whirr of the blades of over 2,000 wind turbines that have been installed.

“If you want to go through here, you can’t, or over there, you have to go around the entire village. There are guards everywhere, protecting the entrances to the wind farms, even though the land is still supposed to belong to the owners. They’ve got me pegged,” says Ná Lupita as she drives her truck down the narrow dirt road, the only one that now enables her to reach the ranch she defended from the Spanish company. Along the paths and roads of Unión Hidalgo, the wind turbines feel closer than in other communities in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; some were set up less than 800 meters from people’s homes.

While Ná Lupita was trying to have her contract rescinded, a French company was preparing its arrival in the village to set up a new wave of “metal and fans.” In 2017, the Energy Regulatory Commission issued the permiso E/1922/GEN/2017 so that Electricité de France (EDF) could generate wind power for 30 years. At that time, according to the stages for the installation of a wind farm, the company already had the studies confirming the energy potential and an environmental impact study. In addition, following the example of other wind energy companies, it had already signed lease contracts after changing the legal status of the land from communal to private property.

Lupita had learned from the previous trial that those contracts should have respected the communal nature of the land and that the approval or rejection of the project was the responsibility of the Assembly of Common Landowners. Ever since assemblies and meetings began to be convened to discuss this new process, she and her cousin Rosario attended them and decided to speak and actively participate in the resistance movement. Together with other women, they formed the Committee of “Gubiña Women in Defense of Life” (Gubiña is the term for residents of Unión Hidalgo), from which they organized to provide information to the people in their town, going from door to door when necessary, and to translate everything that was not understood into Zapotec.

Although she engages in other activities during the day, including caring for her husband, whose illness has progressed during the years of resistance, Ná Lupita has always been willing to go to the briefings, as she does not want companies to take advantage of social inequality.

“We know that they take advantage of people’s need. They come and only say nice things, that they are going to give them money and that they are going to have more work, but that is not true. The only thing that grows is the crime rate where a wind farm is installed,” explains the defender of the land.

The company’s strategies range from providing biased information to giving money to some of the residents or helping schools to gain the support of students. This has polarized residents, weakening the community fabric, and increasing risks and violence against those who defend the territory. For this reason, in October 2020, the Unión Hidalgo community, again accompanied by ProDESC, brought a legal action under “Ley Francesa de Vigilancia” which obliges French companies to respect human rights in other territories where they plan to develop a project.

This is a landmark case, since it is the first time an indigenous community in America has used the mechanism. The most favorable resolutions for Unión Hidalgo would not only be the cancellation of the project, but also comprehensive reparation for the human rights violations that have already been committed. Ná Lupita does not speak French, but she is going to participate in the hearing, because her grandmother taught her to defend those who are unable to do so, which is what she is doing in her village.

EDF has already responded, arguing that it has not violated any human rights, since the organization obliged to undertake the consultation is the Mexican government. The first attempt by the state to conduct this consultation without fully following the guidelines established by the ILO was in 2017. It planned a consultation that would last only three months and only the owners would participate. Matters were complicated by the fact that an 8.2 magnitude earthquake destroyed the community on September 7 that same year. ProDESC requested an injunction from a District Judge which was granted, ordering the Ministry of Energy (SENER) to conduct a consultation in accordance with the highest standards of the indigenous right to consultation and free, prior, and informed consent.

“They did not resume the consultation until 2018 and they continued even though not everything had been rebuilt,” says Ná Lupita in the courtyard of her house that adjoins a house still in ruins after the earthquake.

According to Minutas de las Sesiones informativas de la Consulta, some of the talks were attended by about 41 people, most of whom spoke Zapotec, and were given all the technical and ecological specifications of the project in Spanish.

“They turned up, gave their presentation and started reading. Imagine everything person can say in 30 minutes. Once I said, we are going to ask individual questions about what they have said… Tell me what a consultation is, what a wind energy company is, what this is (….) At that moment all the old women (whom I pointed to) bowed their heads like when you’re at school and you don’t want the teacher to ask you. That’s what it looked like.”

Ná Lupita is convinced that if they really want to provide all the necessary information, the authorities should go from neighborhood to neighborhood, talking to people and answering the same questions over and over again.

During the consultation process, there have been reports of actions ignoring the guidelines defined by the injunction. For example, the process has been financed by the local government, company representatives have participated in the presidium and some workers and students have been forced to attend the sessions.

The COVID-19 pandemic put an end to the procedure, but in July 2021, SENER quiere renovar el proceso it was resumed, without considering the increase in cases of infection or the number of deaths registered in the region.

“Many of the sessions have turned into bouts of shouting and insults, and there were even armed people there. They start shouting when I want to speak, but I stand there quietly, holding the microphone until they quieten down and start listening to me (…) the consultation process is important to see where we stand with EDF”. Ná Lupita is worried that if EDF begins construction, “Then the other companies that have already set their sights on Hidalgo will start coming.”

Lupita has no plans to stop being involved in activism, even though her husband’s health has deteriorated, and he suffered a pre-infarction at the age of 69. Every day she wakes up at five a.m. so she “has time to get things done” and visits her garden that smells of jasmine in the morning. Unlike the wind energy companies and certain politicians, she knows that the land is noble, “They tell us that the lands are infertile, that it is barren land and that they are eventually going to be used by the wind energy companies, but that is not true,” she says in her backyard, where papayas even grow in flowerpots.

In her community, Ná Lupita not only defends and promotes the care and rescue of natural assets, but is also a cautious promoter of religious festivities, ancestral traditions and the accompaniment of other women who wish to become part of the resistance movement and the struggle, “This is the job we were called to do, and I want to continue doing it as long as God gives me strength.”

Some people say Lupita and her companions are “opposed to development” and are “anti-wind energy,” while others use the microphones to shout and prevent their participation, and still others believe that “following Ná Lupe is dangerous.” Once they tried to kidnap her. Her husband was tied up twice in his own business, but they did not steal anything, so they think it was an attempt to intimidate them.

But Ná Lupe does not hesitate to put everything she has at the disposal of the movement and her community, from the time she spends cooking, inviting people to meetings and being an activist, to her truck so that a group of neighbors or journalists can travel or even her house so they can hold meetings and conversations. This is borne out by her patio, which has enough stacked chairs to be turned into an auditorium that can seat at least 25 people.

That integrity and willingness were also on display in the 2017 earthquake, when the community was destroyed and Ná Lupita’s truck was used to sleep outside, drive to the nearest community to fetch food, and supplies and transport the tools and material required to help those who had lost everything.

When an organization donated a community kitchen for Unión Hidalgo, Ná Lupita did not hesitate to accept it and allow it to be built on one of her plots of land. That kitchen served up to 100 breakfasts and 100 lunches a day to those who did the reconstruction work, and subsequently became a source of income for some of the women who had organized. The pandemic put an end to the dining room project but opened a window to use the space as a community COVID-19 information center.

Those who have accompanied Na Lupe in her development process, consulted for this story, have even seen her present her case at national and international human rights forums. They think she has grown and lost her fear of public speaking, although the lack of response and resolution of the case has taken a heavy toll in emotional and family terms.

This report is part of the Defenders of the Territory project sponsored by Climate Tracker and FES Transformacion.

Leave a Reply